ITPNZ and NZCS: A history spanning 60 years (1960–2020)

As the oldest tech body in the country, IT Professionals New Zealand, previously the New Zealand Computer Society, boasts a proud and colourful 60-year history. Throughout these 60 years, ITPNZ has been a strong and unwavering advocate for IT education, and has provided rich and independent advice, guidance and advocacy to government, the industry, the profession and the public.

This short history has been written over many years and incorporates a summary of the first 15 years by John Robinson, the following decade by Bill Williams, then the remainder assembled and written by current ITPNZ Chief Executive Paul Matthews, with contributions and assistance from many of the society’s fellows and long-standing members.

1960–65

The Data Processing and Computer Society was registered by the Registrar of Incorporated Societies on 6 October 1960, with these original members: Gordon Oed, WL Birnie, EW Jones, AW Graham, P Walker, HF Foster, JG Miller, JV Robinson, JJ Campbell, AS Carrington, SR Searle, ADG Connor, WJ Wills and J Martin. The name was changed to the New Zealand Computer Society on 20 February 1968.

When the inaugural meeting was being set up and the draft constitution was being prepared, the main topic of concern and discussion (and a rather surprising one in retrospect) was the need to ensure that the machine houses did not take control of this new society and make it a promotional, rather than a learned one. At least, for those who had been exposed to this view, the way each of the companies formed a phalanx of staff in the Victoria University lecture room at the first meeting seemed to justify this concern. In hindsight this was much more likely to have been due to the fact that they preferred to sit with people that they knew and that company management wanted to help the society get started by ensuring that it had as many members as possible, rather than to any covert intention. However, voting membership was limited to two from each company until the constitution was changed in 1970.

Wellington branch was the first, with Canterbury, Otago and Auckland branches following, but there was very little activity on a national basis. The affairs of the society at that level were in the hands of an executive committee which met very infrequently. A Wellington-based standing committee dealt with detailed organisational matters for the executive. By 1965 there were over 200 members in the established branches, Wellington and Canterbury, and Otago and Auckland branches were forming up. This growth made it clear that there needed to be a re-assessment of the society and its role.

This was discussed at the executive meeting in October 1965, where it was agreed that the constitution needed review, that the possibility of holding national conferences and of publishing a journal should be assessed, and that nationally organised lecture tours by overseas specialists were still not practical.

1966–70

During these five years the society underwent a major rearrangement and national affairs began to increase in importance. A postal ballot was held in 1967 to get the view of the membership on a change of name, and on the membership restrictions on machine company staff. There was also a growing concern about the lack of formal education in computing in New Zealand.

Auckland ran the first national conference in 1968. Its success and the opportunity which it gave for a wide section of the membership to discuss the society, its future direction and some of the issues facing the computer industry, such as education, gave a great impetus to both the national activity and overall coherence in the society.

The executive and the standing committee amalgamated in order to cope with the tasks with which society management had been charged. A report was prepared on the role of the universities in education and research in computing. The Technicians Certification Authority was approached to see whether they would consider extending their certificate to include computing. The constitution was completely rewritten. The grade of ‘member’ was established to identify the ‘competent computer professional’. Organisationally the society was changed from a reasonably loose alliance of individual branches to a national organisation. The implementation of this change was a good deal more gradual than the constitutional change that gave it form.

By the time the second national conference was held in 1970, however, the stage was set for an effective national organisation.

1970–75

While total membership numbers stayed static over this period there was a shift from associate member to member that resulted in a doubling of the number of members. This typified the changes in this period — a shifting emphasis on creating a professional society. Associated with this, there was acceptance by both the government and the public generally, that the society was representative of the computer practitioners of this country. The society responded to this acceptance with an examination of some of the social issues related to the use of computers. This was undertaken not only from a sense of social obligation but also because it was felt that some self-regulation by the industry over issues such as privacy could prevent crippling legislative constraints on computing.

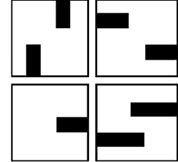

During this period the society adopted its first logo in the form of four squares, suggesting four punch cards, each showing one of the letters NZCS. The logo was selected from 41 entries in a competition held in 1971, the winning entry being submitted by Paul Compton of Wellington. The first edition of the society’s quarterly Bulletin made its appearance in October 1973. It was much enlivened by the occasional cartoon from its editor ‘Slim’ Burns.

In the field of formal education, the society was instrumental in getting the Technicians Certification Authority to institute the New Zealand Certificate in Data Processing in 1972. Support of this part-time course has been good and justifies the effort that it took to get it started. While not so direct in effect the report produced by the society on university education and research helped create a political climate that fostered the growth of computing education in the universities.

Conferences continued to be outstandingly successful and became a well established and valuable part of the society’s activities.

The minimum necessary standard of experience set for transfer to the grade of member continued to improve. Union membership also became an issue, as the growing size of the industry and the differences between computer and clerical work become less marked.

A major activity in the early part of this period was that arising from a motion proposed at the Dunedin conference, that the society investigate a unique identification system to facilitate communication. The original suggestion had been that the study be restricted to commercial communications, but members opted for the wider study. After very full discussion and debate in the society the committee tabled its report which found, inter alia, that it saw no grounds for establishing unique identifiers for use on a nationwide basis. The report was eventually endorsed at a special general meeting in 1972.

1975–80

The opening years of this period saw three important projects brought to a conclusion.

The code of ethics, which had been debated for over three years, was agreed following consideration at two special general meetings in 1976 and 1978. By general consensus the code was to apply to all three main grades: fellows, full members and associates.

The other two projects were related, being the question of registration of computer practitioners and the requirement to join unions. The society’s view on registration was that the time was not opportune for such a move, but if it were to be contemplated the society would wish to be involved in the formulation of the rules and possibly the administration. In the event the government did not follow up the original suggestions. The debate on joining unions centred around programmers who, the union claimed, were carrying out clerical functions. A special committee set up by the society to handle the matter established a good relationship with leading union officials and especially with the Clerical Workers’ Union. In the end the status quo was preserved.

The previous period had also witnessed much public and professional concern over proposals for the Health Department computer system. Society members expressed disquiet on two counts: that the prime contractor had been appointed without public tender, and that the system they proposed was unworkable. As a result formal representations were made to the Minister of Health, and the president, who later reported that ‘While the Health Department officers were able to quite adequately assure me on the Society’s concern relating to the appointment of the consultants, I cannot report that I was equally well satisfied on the degree of technical assurance applied to the acquisition of this major system.’ Subsequent events were to prove the society’s reservations were well founded.

Several procedural changes were made during this period to improve efficiency and lighten the burden of administration. Firstly, the central membership system now in use was introduced; secondly, changes were made to the constitution to bring it more into line with modern practice; and thirdly, the quarterly Bulletin was replaced by a monthly newsletter published in every issue of the journal Data Processing in New Zealand.

Two important reviews were carried out. The first, in conjunction with Victoria and Massey universities surveyed data processing staff in New Zealand, and the second looked at the profile of society membership. The latter pointed out that while society membership appeared to cover a satisfactorily wide range of occupations, there was low representation from government departments, computer engineers, operators, young people and ‘interested amateurs’. It was therefore suggested that recruitment of members should be especially concentrated in these areas.

The subject of privacy raised its head many times during the period. The society played an active role in shaping the Wanganui Computer Centre Act and its subsequent revisions. It was invited to make nominations for the committees to be established under the Act and one of its nominees was eventually accepted. Nationwide publicity was given to the society’s stand on the question of the proposed sale of computer records by a city council. The society established its general guideline, later to be expanded into a full position paper, that ‘personal information should be used only for the purposes for which it was given’.

Much effort continued to be put into the fields of education and consideration of the impact of computers on society. Typical examples were a most successful series of continuing education seminars and further useful dialogue with the unions on the introduction of computers in the workplace, culminating in the sponsorship by the society of a visit to this country of Kristen and Johanna Nygaard.

1980–85

The 1980s found the society becoming involved, to an ever increasing extent, in a wide range of activities. More and more the society was being consulted on matters relating to computing in all facets of law, government and society, visible proof of the success of early efforts to raise the society’s profile.

The extent of this involvement can be gauged from a list of activities taken over a three-month period in 1980. They included submissions to or work for:

- the Auditor General in his review of computing in the public sector.

- the Planning Council in response to their position paper ‘An Employment Strategy for the 1980s’.

- the Communication Advisory Council on the impact of view-data type systems.

- the State Services Commission on amendments to the Wanganui Computer Centre Act.

- the New Zealand Product Numbering Council — Adoption of Product Numbering Standards for New Zealand.

- the Committee on Official Information.

- a revision of the Electoral Roll.

It was apparent that all this was placing too great a workload on volunteers from the membership and that more support for committees and project teams was imperative. It was for this reason that, when the secretary retired at the end of 1980, he was replaced by a part-time executive secretary, the late Bill Williams. This was seen as the first step towards the society having available the services of a full-time national staff and office, eventually achieved in 1983 when Williams became the society’s first full-time executive officer.

Bill Williams was instrumental in bringing about law changes related to the Wanganui Computer Centre, Election Reform, the Crimes Act (as it affected computer crime), the Copyright Act (relating to the protection of computer software), and provisions for protection of personal information. Williams also set up a joint study group with the Law Society, the Human Rights Commission and the Medical Council, which resulted in an agreed position on how those holding personal information should respect the privacy of individuals. This was widely accepted and adopted and later formed the core of New Zealand’s privacy legislation. Williams also edited the NZCS 25th Anniversary Book, Looking Back to Tomorrow: Reflections on Twenty-Five Years of Computers in New Zealand.

It was also agreed that the opportunity for a greater degree of continuity should be given to councillors and the president and in both cases the initial term on election was changed from one to two years. More emphasis was placed on forming project teams, not necessarily restricted to councillors, to undertake specific activities.

The society achieved a new high in the number of its publications. It produced its first book Choosing Your First Computer System, two position papers (on privacy and education), a booklet listing consultants, counsellors and expert witnesses, a further booklet on Guidelines on Privacy — Security — Integrity, and a NZCS Year Book. It adopted a new logo and changed to the magazine Interface for the regular dissemination of information to members. Another first was the concept of an inter-conference year mini-conference. RUTHERFORD 84, restricted to members, with New Zealand speakers on the theme of communications presenting in a lighter vein, was voted a great success by those who attended. This conference led to the establishment of the Telecommunications Users Association of New Zealand (TUANZ) in 1987.

However, if one activity were to be highlighted it would be that of education. The society’s Continuing Education Programme was strengthened and put on a professional footing by the appointment of a Director of Continuing Education, which enabled an ambitious and successful programme of seminars to be launched. NZCS also helped establish the Computer Education Society, both at a national level and a number of regional Computer Education Societies. These were the first computing teachers’ associations in New Zealand, and were a driving force in providing a voice and community for those interested in computing education and in promoting the use of ICT in schools.

NZCS also played an active role in the deliberations of the Consultative Committee on Computers in Schools and with the Vocational Training Council took active steps to improve the professional standing of its members by setting new requirements for advancement to the professional grade of full member. Greater emphasis was given to the acquisition of formal academic qualifications.

1985–90

Additional regional Computer Education Societies were formed in the mid-to-late ’80s in several regions around New Zealand and, together with NZCS, contributed to a raised profile and participation of computing education in schools.

The profile of the society was raised significantly when president Jim Higgins became famous for his regular morning slot on National Radio, educating the public about all manner of computing and IT matters. Higgins continued the slot for 20 years, finally hanging up the microphone in 2009.

This period was also famous for a refusal of the society’s annual general meeting to accept the annual accounts due to what appeared to be a significant unexplained drop in funds. In actuality this was mainly due to an employment dispute and payment, which was the subject of a non-disclosure clause, with the president and national council unable to discuss or even disclose its existence, resulting in a very long and tense AGM. With nobody wanting a repeat, the subsequent special general meeting passed the accounts in record time; so fast, in fact, that Computerworld reporter Stephen Bell was almost trampled by the members beating a hasty retreat when he arrived a few minutes late.

In 1987 PriceWaterhouseCoopers partner Phil Parnell was elected president and worked tirelessly to improve the structure and financial footing of the society.

In 1988 Drew Bond (who later became president) penned a discussion paper on health information policy for the then Department of Health, foreshadowing much of the subsequent policy in this area.

Over this time the large national and smaller Rutherford conferences were hugely successful, being the annual events for the sector. Additional events in conjunction with the International Federation for Information Processing (IFIP) and Association of Computer Machinery (ACM) led to a very full calendar of events.

On the international stage, the society scaled down activities with IFIP amid some protest from longer-standing members, and instead joined the South East Asia Regional Computer Confederation (SEARCC) with a view to contributing more significantly to the Asia Pacific Region. Through president Philip Sallis, NZCS also participated strongly in the ACM Computer Science Curriculum and Research Committees in Hong Kong and New York.

1990–95

Having been at the forefront of advocacy around privacy and the protection of personal information, the society was heavily involved in the establishment of New Zealand’s Privacy Act 1993, enshrining several key NZCS privacy and information-related positions from the previous decade.

The society continued to be well served by strong advocates to government including Jim Higgins and the late Bill Williams, with president Philip Sallis also chairing the government’s Consultative Committee on Information Technology and serving on the Science Curriculum Task Group and the Information Technology Advisory Committee.

1994 saw the appointment of Ian Mitchell as president. Mitchell embarked on a strategy of rebranding and refocusing NZCS, and strengthening the society’s links to education in schools and the tertiary community.

Mitchell had strong views regarding the direction of the society and was known for his ‘100 ideas a minute’ approach, ranging from the genius to the not-so-brilliant, however, he was a dedicated and hard working servant of the society.

1995 also saw the establishment of the Internet Society of New Zealand (ISOCNZ), later renamed InternetNZ. While not directly linked to NZCS, many of those involved in the establishment of ISOCNZ were also involved with NZCS and ISOCNZ was seen by many as a kindred body.

1995–2000

The operational structure of the society was changed in 1996 with the establishment of the society’s first chief executive position (previous appointments being executive officers). The appointment of recruitment agency the Doughty Group founder Beverley Pratt was not without some initial controversy, primarily due to the choice of someone with a strong commercial background, which was somewhat of a departure from the previous custom in the society. The appointment of a female chief executive in such a male-dominated industry also raised some eyebrows, but was met with approval from most, especially when Pratt excelled in the role.

The move to a chief executive, especially one with commercial experience, marked a gradual shift in how the society operated. In previous decades it had been run almost entirely by volunteers, with the president being a close to full-time role and volunteers often paid by their companies to participate. However, society in general was changing, and the time people could contribute was diminishing.

1999 saw the appointment of the society’s first, and to this date only, female president in Gillian Reid. Gillian was very keen in reviewing the criteria for membership and advancement, including modernising the process of becoming a fellow from being nominated to applying, and establishing a new honorary fellow (HFNZCS) title for those the society wished to recognise and honour. A council ‘committee of two’, being Gillian and Ian Howard, was set up to look at options. Their simple task was to come back with new criteria for levels of membership and criteria for advancement, including moving the process of becoming a fellow from being nominated to actually applying.

Gillian was heard to comment that climbing Mt Everest without oxygen would probably have been easier. It took the two of them many months of hard work, several iterations to council for review, and then a survey of all the members following council’s final agreement on the new membership structure. They survived, just, and the new structures were put in place in 2000.

2000–5

Upon joining the South East Asia Regional Computer Confederation (SEARCC) several years earlier, NZCS had agreed to organise and host the annual SEARCC international conference in 2001. Unfortunately the date of the conference was November 2001, two months after the 9/11 terrorist attack. The effect was dire — almost all international delegates, especially those from anywhere in Asia, immediately cancelled their registrations. Ditto for most of the over 50 Australian Computer Society (ACS) members already registered, as there were ‘no flying’ instructions sent out to employees of almost every company of any significance as a reaction to the attacks. The society stood to lose significant funds from the conference.

The Australian Computer Society went into bat for NZCS, trying to obtain a commitment from SEARCC to underwrite any significant loss from the conference from their substantial funds, or even just loan the difference to NZCS so that creditors could be paid. The confederation was deeply divided on the issue, which caused much friction. When the dust settled the SEARCC secretary general had resigned, but alas still no support. Indonesia then withdrew from hosting the 2002 SEARCC Conference, citing concerns over cost and liability.

At the time, NZCS branches maintained separate funds, and ended up contributing to what was eventually a relatively minor loss, and the conference went ahead with about 220 attending. By all accounts it was an excellent conference.

Around this time early stage discussions were instigated by vendor body the IT Association of New Zealand (ITANZ) about forming an umbrella IT group made up of ITANZ, the Internet Society (InternetNZ), the Telecommunications Users Association (TUANZ), NZCS and the Software Association, with TUANZ rejecting the idea outright and all other groups being lukewarm at best. These discussions would continue for several years, culminating in the ICT-NZ proposal that would end up causing great division in NZCS.

The following years saw the society take positions on a number of issues, such as the inadequacy of contracts many software developers operate under, and in 2004 instigating structural governance changes, halving the size of the national council and increasing the council voting power of the two larger branches.

2005–10

In 2006 the ICT-NZ concept and proposal, where the major IT bodies would effectively merge into one larger group, was at the fore of discussion. A group primarily from the Auckland branch of the society were pushing for the society’s entry into ICT-NZ, gaining support to continue looking into it from an at times heated and somewhat controversial AGM in 2006.

The discussion and consultation that followed resulted in a deep divide at all levels, from national council to branches and among the membership, pitting branch against branch in a robust and at times bloody debate about the future of the society. Proponents saw the ICT-NZ model as a way forward for what had become a relatively inactive and (some believed) irrelevant society, where the future could be secured as part of a larger group with the carrot of government funding. Those opposed felt that the profile, culture, purpose and objectives of the society would be lost, that the needs of a professional body were different to those of a vendor group, that the new body would access the society’s revenue stream, matched by government funds, but then use it to further activities that were not core to the society’s purpose, and that NZCS had the potential to be the body leading much of the work that was important to the organisation anyway. There was also nervousness about the implication that ICT-NZ was a government-promoted and funded body, and up until then NZCS had been fiercely independent — from government and vendors.

Wherever the truth lay, the main debate was in relation to what was termed the ‘One World Government’ approach of all organisations becoming one, versus the ‘United Nations’ approach, with all participant organisations maintaining their own identities but coming together to form an IT Council to collaborate in areas of mutual interest.

The debate dominated society activity and discussion for well over a year with other activities grinding to a halt. The matter came to a head in early 2007 with a series of motions put forward by the NZCS Auckland Branch to force a binding referendum and commit the society to joining ICT-NZ, countered by a series of motions from Wellington branch disbanding the working group established to consider the idea, and putting any plans on hold until other, more representative, models could be at least considered.

Following much heated debate, the Wellington motions succeeded and any decision on the ICT-NZ model was deferred for ‘at least’ six months. President Richard Donaldson’s casting vote was used to disband the ICT-NZ working group with all other motions passing with a clear majority. One of those spearheading the call to look at other options first, Don Robertson, was appointed to lead a new working group bringing together wider options to be considered, and later became the next president. Another, Paul Matthews, went on to become chief executive and lead a programme of change within the society.

The debate and fallout from the decision had caused a deep division in the society. However, it had also resulted in much consideration into the purpose and future of the organisation and can be credited with focusing the new leadership to returning to the previous times where NZCS was significantly active in education (school, tertiary and ongoing), advocacy, government policy and other activities.

The decision spelt the end of ICT-NZ, with the government pulling all funding and instead forming the NZCS-supported Digital Development Council, similar to the ‘United Nations’ model put forward by NZCS and others and not subsuming identity. The funding of this didn’t survive the 2008 election and the body disbanded in 2009, leading many to wonder whether the promised ICT-NZ funding would have met a similar fate had the society gone down that track.

One of the first issues tackled by the new leadership was the dismal state of computing-related achievement standards in schools, with the society commissioning a report looking into the issue penned by Auckland teacher Margot Phillipps and AUT academic Gordon Grimsey, and reviewed by 13 academics and senior professionals throughout New Zealand.

The report found that none of the existing IT achievement standards were suitable for the assessment of IT, which led to significant advocacy activity spearheaded by the new chief executive and major changes to the way computing and IT was taught in schools. This included a new digital technologies curriculum, a full set of new achievement standards, updated unit standards, and additional teacher resources to improve the standard and consistency of learning in the field of IT.

2010–15

This was very much a growth period for the organisation, with an expansion of the refocus on being a professional body ushered in by the new leadership and with broad support from members.

Over the next few years the society’s renewed focus was translated into specific initiatives such as the implementation of the IT Certified Professional (ITCP) accreditation, which became Chartered IT Professional NZ in 2015, a revised mentoring programme, work towards implementing internationally aligned industry accreditation of tertiary degrees, plus a host of other projects.

Ray Delany, a tech leader from Auckland, was appointed President in 2010 and held the role until 2014, when Ian Taylor, of Animation Research Ltd fame (later to become Sir Ian Taylor) took on the presidency, and both were pivotal in continuing the growth of the organisation.

NZCS changed its name to the Institute of IT Professionals NZ (later shortened to IT Professionals NZ) in 2012, following significant membership consultation and with support from 97% of members. This new name matched the new focus of the organisation. NZCS also re-established national conferences, starting with a bumper conference in 2010 marking 50 years of tech innovation, with a host of industry heavyweights speaking and attending.

Over this time the society also became active again in advocating issues such as copyright, promotion of education and skills, and a host of other initiatives and advocacy areas, once more establishing itself as the voice of the IT profession. And then came the battle against software patents.

The changes to the Patents Act in New Zealand started in 2010 when the Commerce Select Committee, reviewing proposed changes to the Patents Act, recommended that software be excluded, following submissions by the New Zealand Open Source Society and others outlining the dangers of software patents to the tech industry.

All hell broke loose, and an intensive lobbying effort commenced, led by the pro-patent fraternity. Certain large multinationals invested heavily in the outcome, concerned that a removal of software patents in New Zealand would cascade to other countries. In some respects it pitted the multinationals against the New Zealand industry, with a poll at the time finding 81% of IT professionals supported the removal of software patents.

However, in the end, following consultation with the Select Committee, Simon Power (the Commerce Minister at the time) reaffirmed that the proposals wouldn’t be modified. The blog post NZCS CEO Paul Matthews wrote announcing this to the world was massively welcomed by the tech industry globally. It was duly ‘slashdotted’, retweeted extensively and seen by over a million people, with tens of thousands of tweets and messages of congratulation to New Zealand.

Fast-forward to the 2011 election, and Simon Power stood down and Craig Foss became Commerce Minister. With a new minister, lobbying efforts to revert the Bill began again in earnest, this time primarily led by patent lawyers. The new minister changed his tune and reversed the changes.

So NZCS took a different approach.

The Parliament at the time was made up of 121 seats, with 61 needed for a majority to pass a new law. National held 59 seats and were supported in coalition by ACT (one vote) and United Future (one), and sometimes the Māori Party (three) instead. The Patents Amendment Bill was a huge revamp and update of the Patents Act of 1953, and generally had widespread support across Parliament.

NZCS was in close contact with all parties about the issue, and Clare Curran from Labour was able to secure support from her party to vote against the new Patents Bill, unless the software patent issue was resolved to our industry’s satisfaction. The Greens, New Zealand First and the Māori Party also confirmed they’d vote with the industry on it, despite also generally supporting the Bill as a whole.

However, the National government still had the numbers to pass the Bill with the support of ACT and United Future. ACT didn’t want to know; they confirmed that they would be supporting National no matter what. But United Future’s Peter Dunne took a different approach. He spent considerable time getting to grips with the issue, finally confirming that United Future would also vote against the Bill unless the issue was resolved — and with that, the government no longer had the numbers to pass the entire Bill unless they came to the party on banning software patents.

The government found themselves on the wrong side of the bulk of the local IT industry, and in the position of not being able to advance a major piece of legislation because of one small section. And so, the negotiations began.

Much of the negotiations over the following weeks and months happened behind closed doors, but NZCS was in the position to negotiate directly with the government on the software patent exclusion, supported pro-bono by several lawyers closely linked to NZCS. The organisation held our ground, liaising with the NZOSS, InternetNZ, NZRise and others, until a solution was found.

The resulting section of the Patents Act bans software from patentability. Lawyers like to argue and there is still debate about what this actually means, but basically software itself, such as Amazon’s 1-click, isn’t patentable in New Zealand.

The local tech industry had won.

2015–20

ITPNZ (as it was now) had a strong focus on reforming tech-related education over this period, starting with the digital technologies curriculum in schools, but also taking a leading role overseeing the rewriting of all sub-degree qualifications recognised in New Zealand and implementing degree accreditation on behalf of industry.

The new NCEA achievement standards at senior secondary level, implemented as a result of the earlier work, were put in place in 2011–13, however, the work to roll this out through the rest of the school system had stalled. ITPNZ advocated strongly to the minister and Ministry of Education and eventually won a review.

This review, with heavy participation from ITPNZ, led to what is now known as the Digital Technologies and Hangarau Matihiko curriculum changes, the most significant changes to the school curriculum since it was introduced a decade earlier. These introduced digital tech formally into the curriculum at all levels, including compulsory provision in all schools from years 1–10.

ITPNZ also launched an initiative called Tahi Rua Toru Tech to help introduce and support digital technologies in schools, funded by both industry and the Ministry of Education. This saw small groups of school students finding a problem in their local school or community and using digital technologies to solve it, with an industry mentor and lots of resources. Thousands of students participate in Tahi Rua Toru Tech every year, culminating in regional and national finals and an awards event where the top student teams in the country are celebrated and recognised.

At the tertiary side, ITPNZ worked with the New Zealand Qualifications Authority to review all sub-degree qualifications in New Zealand, with ITPNZ assembling and leading the governance group for the review. This resulted in scrapping all 224 existing qualifications and, following extensive industry consultation, developing twelve new qualifications that mapped directly to industry needs. These are now taught in most polytechnics and many private training establishments across New Zealand.

ITPNZ also implemented formal industry accreditation of tech-related Bachelors degrees, linked to the Seoul Accord — an international cross-recognition agreement between countries. Many universities and polytechnics underwent the accreditation process and later ITPNZ signed an MOU with Engineering New Zealand and the New Zealand Qualifications Authority for joint accreditation processes.

Tauranga tech entrepreneur Mike Dennehy was president for most of this period, taking over from Ian Taylor in 2016 and serving a full four-year term until 2020. Mike helped broaden the organisation’s focus around professional practice and collaboration.

In 2016, ITPNZ combined with eleven other tech bodies to produce a large collaborative conference called ITx, focused on Innovation, Technology and Education. This conference was conceived and run by ITPNZ and became the largest independent tech conference in New Zealand, running every second year with a smaller regional conference in the other years. ITx was a huge success and also saw the introduction of the New Zealand Excellence in IT Awards. While the industry already had the well-established HiTech Awards, these focused mainly on celebrating the success of tech companies, whereas the Excellence Awards focused on individuals and teams in the tech sector. These awards were well supported and have helped recognise dozens of tech professionals across the country.

In 2017, ITPNZ was gifted the te reo Māori (indigenous New Zealand) name Te Pou Hangarau Ngaio, which recognised the journey the organisation was taking to becoming more inclusive. This name reflected ITPNZ’s role in the tech community:

- Te Pou: the centre pole, the central post of a building such as a marae, i.e. the main support

- Hangarau: the generally accepted word for technology

- Ngaio: experts or professionals

So Te Pou Hangarau Ngaio essentially means the central pole or structure supporting technology professionals.

In 2018, ITPNZ also began providing qualifications assessments for immigration purposes, to offer pathways into New Zealand for those with the skills needed but without a degree that directly mapped to a New Zealand tech-related degree. This included a formal assessment of all learning, and if it met the general expectations of a tech degree, certifying this for Immigration New Zealand.

The organisation’s skills focus continued in 2020, taking ownership of the skills work stream of the Digital Technologies Industry Transformation Plan — creating a blueprint for changes to the skills and education system in New Zealand to enable rapid growth of the tech sector. This work continues into 2021 and on to the release of the plan.

After 60 years, ITPNZ is a strong, growing and contemporary organisation with a broad range of projects and initiatives for and on behalf of the tech community and thousands of members across New Zealand. While recognising its heritage and history, ITPNZ continues to lead professional development and good practice in IT into the 2020s and beyond, changing as the industry changes and meeting the needs of professionals.

Where to from here?

There is still plenty of work to be done. 2020 saw major government reforms in areas such as education, along with a massive increase in cybersecurity breaches and incidents, and huge challenges as a result of COVID-19.

The tech industry has a huge role to play in New Zealand’s economic future and it’s essential that organisations like ITPNZ continue to support and grow the industry, while providing independent advice to government and others as they navigate digital technology.

60 years? We’re only getting started.