Challenging technologies: Perspectives from the Privacy Commissioner

John Edwards & Lauren Bennett*

* This book is published just a few months after the Privacy Act 2020 came into force, an event which has prompted many information professionals to review how their work can ensure the privacy of the personal data that is an essential component of our work. The Office of the Privacy Commissioner (OPC) works to develop and promote a culture in which personal information is protected and respected. Part of that work is building and promoting an understanding of the privacy principles, and it offers free online privacy education. ITP invited the Privacy Commissioner to discuss privacy, technology, and the role and responsibilities of IT professionals. In April 2021 the Privacy Commissioner John Edwards met with Lauren Bennett for a wide-ranging discussion on how technology challenges privacy, and how privacy regulation can also challenge technology; this chapter is a condensation of that discussion.

While we can say that the fundamental right to privacy is a feature of human dignity, it is a very wide and contextual topic, and its application often requires adaptation to meet new technological challenges. Leaps in privacy law have very often followed technology. In New Zealand our legislative approach has been technology neutral. That has stood the law in good stead and has enabled it to adapt to changing technological environments in the last 28 years since the first Privacy Act in 1993.

The historical development of privacy and data protection

In 1890 a seminal paper was published in the Harvard Law Review written by Warren and Brandeis, both of whom went on to become Supreme Court judges in the US; it was called ‘The Right to Privacy’ (Warren & Brandeis 1890). In it they considered whether there was a principle to protect the privacy of the individual, and if so then what is the nature and extent of that protection. A catalyst to their article was that they considered:

Instantaneous photographs and newspaper enterprise have invaded the sacred precincts of private and domestic life; and numerous mechanical devices threaten to make good the prediction that ‘what is whispered in the closet shall be proclaimed from the house-tops’ …The press is overstepping in every direction the obvious bounds of propriety and of decency. Gossip is no longer the resource of the idle and of the vicious, but has become a trade, which is pursued with industry as well as effrontery. To satisfy a prurient taste the details of sexual relations are spread broadcast in the columns of the daily papers. To occupy the indolent, column upon column is filled with idle gossip, which can only be procured by intrusion upon the domestic circle.

Warren and Brandeis were concerned that the development of this new technology called instantaneous photography was going to destroy privacy amongst Boston socialites, and that everywhere they went they would be snapped and featured in the gossip columns of the local papers.

In NZ there were a range of laws that regulated certain kinds of privacy invasion, for example it was an offence to disclose the contents of a telegram (1884) or a letter (1919); and it was a crime to peep or peer into the window of a dwelling house (1960). But privacy was not seen as something that needed specific legal protection until the mid-1970s.

In the 1970s a shared computer infrastructure called the Wanganui Computer Centre was built to house a mainframe computer that was going to be available to more than one agency across the law enforcement sector. That caused great concerns about privacy and the ability of agencies to share information and move it very rapidly, particularly information that had been collected for different purposes. People from all walks of life were concerned that it could be repurposed as a tool of an oppressive state. The legal response to that controversy was passing a very proscriptive and restrictive law called the Wanganui Computer Centre Act 1976, the purpose of which was to ensure that the system made no unwarranted intrusion upon the privacy of individuals. The Act did this by limiting the type of information authorised for storage, and the purposes for which agencies could access information added by their colleague agencies.

That concern about the potential for computing to impact on privacy was an issue not just in New Zealand; it was an international concern, particularly around the movement of information across jurisdictions around the world. With the introduction of information technology into various areas of economic and social life, and the growing importance and power of computerised data processing, the OECD in 1980 decided to issue guidelines governing the protection of privacy and transborder flows of personal data (OECD 1980). That response was limited to informational privacy, which is the ability to control the collection, use and disclosure of personal information, rather than other domains of privacy like spatial privacy, which is the right to protect a person’s physical and psychological integrity from illegitimate invasions, such as the right to be let alone and the right to protection from unreasonable search and seizure. This articulation of privacy in some jurisdictions is called data protection. So, half the world calls the law based on those OECD principles data protection, and the other half calls it privacy. Those principles that the OECD set out have been quite enduring: they formed the basis of our 1993 Privacy Act, they were reviewed by the Law Commission and were found to be sound and still relevant, and so formed the core of the 2020 Privacy Act. We see them also being the basis for the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and most other privacy or data protection regimes in the world.

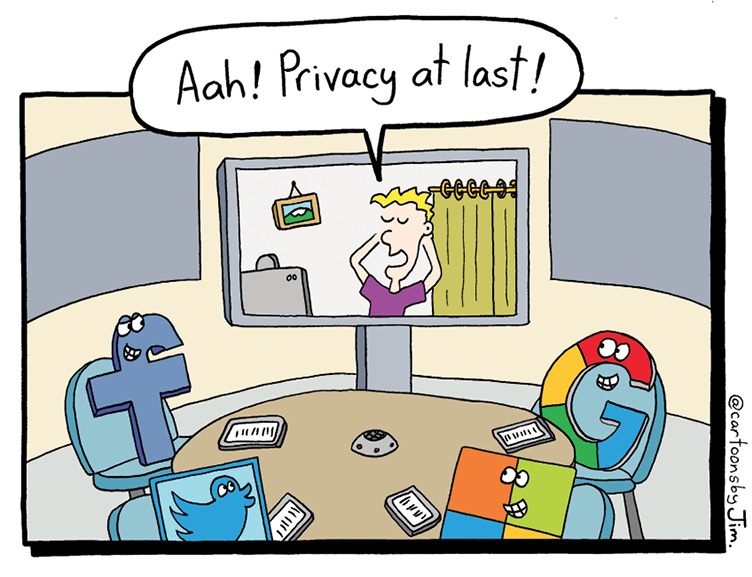

Now we are seeing technology throw out new challenges that the last generation of data protection or privacy law struggles to cope with. For example, we have seen around the world in recent years parliaments and lawmakers really grappling with how to deal with all the social impacts of social networking, a technological phenomenon that has a range of implications and potential harms for individuals and societies, of which one is privacy.

Digital technologies challenging privacy regulation

Democratisation of digital technology

One phenomenon which really challenges privacy can be described as the democratisation of digital technologies or the retail availability of these very intrusive technologies. So while we can say that in certain cities such as San Francisco and Boston the police institutionally are not able to use facial recognition in public spaces, anyone can download an app right now that is able to take a photo and match it with an online profile. This poses huge risks for people who may have very good reasons to maintain different personas, who legitimately want to present a face in their social media which is quite different from the one that they use in their work or in their private life.

The point about retail availability is that it is very hard to control, and the challenges to regulate technology are huge. A good example is encryption technologies. In the 1990s the Clinton administration tried to ban the export of PGP (pretty good privacy) encryption technology by classifying it as a strategic military technology. The creator responded to that by publishing the entire source code for PGP in book form (Zimmerman 1995) so it was protected by the first amendment, but as each page could be removed and was machine readable export controls were avoided.

More recently Australia passed the Assistance and Access Act 2018, an anti-encryption law that can require communications services providers to assist the police and other agencies when requested. At the time people claimed that trying to legislate against encryption was like trying to ban the laws of mathematics. The Prime Minister said, ‘The laws of mathematics are very commendable but the only law that applies in Australia is the law of Australia.’* The battle between emergent and ubiquitous technologies and this kind of social legislative response to them is not very sophisticated at this early stage, and the blunt understanding that new technology can be used for ill is ultimately pretty unproductive.

* Knott, M (2017). Facebook rebuffs Malcolm Turnbull on laws to access encrypted messages for criminal investigations. The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved from www.smh.com.au/federal-politics/political-news/facebook-rebuffs-malcolm-turnbull-on-laws-to-access-encrypted-messages-for-criminal-investigations-20170714-gxb773.html

Live-streaming

Another technology development, of which I have been very critical, is the now ubiquitous availability of live-streaming technologies, in forms like Periscope, Facebook Live is the obvious one. These technologies can reach an enormous audience, are capable of causing great harm and yet are deployed in this mad rush to market. The first-mover advantage means just because a company can do it then they should do it; move fast and break things and at some point further down the track turn around and look at what has been broken. This is hugely challenging and problematic, and I’ve been very critical of some of the technology leaders for acting irresponsibly in this space.

For example, if Facebook had undertaken a thorough Privacy Impact Assessment of its open-to-all live-streaming feature before deploying it, it might well have identified the risk that a terrorist such as the Christchurch shooter would use the feature to distribute and amplify his message. That early identification might then have led to the development of an AI to detect and interrupt such outrages before they could be widely distributed. In the event, Facebook imposed constraints after March 15 which, had they been in place at the time of the attack, would have prevented the atrocity from being broadcast on their platform.*,**

* Rosen, G (2019, May 14). Protecting Facebook Live from abuse and investing in manipulated media research. Facebook Newsroom. Retrieved from newsroom.fb.com/news/2019/05/protecting-live-from-abuse/

** Pullar-Strecker, T (2019, May 15). Jacinda Ardern says Facebook Live crackdown shows Christchurch Call is being acted on. Stuff. Retrieved from www.stuff.co.nz/national/christchurch-shooting/112738084/facebook-imposes-one-strike-bans-for-serious-breaches-of-its-live-streaming-rules

Facial recognition

If you compare the deployment of live-streaming with facial recognition and AI, some technology firms have said that they are not going to make this technology publicly available. That means they lose the first-mover advantage. When Google says, we are uncomfortable with facial recognition, then Clearview AI steps into this space, arguably less principled, less transparent, less accountable, and starts offering this retail technology to individual police officers, sidestepping institutional checks and legislatures.

AI

Artificial intelligence is a huge topic that is going to transform society. We are only at the tiny bottom point of it, yet we already get enormous benefits from it in ways that most of us do not appreciate. Pick up your phone and say, ‘Show me photographs of a cat.’ The phone knows what a picture of a cat looks like and that is artificial intelligence, it is machine learning, which is hugely important because of course we all need quick access to cat photos. The fact that there are benign or socially beneficial uses doesn’t mean we shouldn’t confront the very great potential for harm.

The big and obvious concern is that the artificial intelligences are only as good as the data inputs, and when you train a machine learning functionality based on data which is already infused with the inequities and biases of our imperfect society you can really exclude people. We make these heroic assumptions about the neutrality of technology. One of my favourite examples in this space, although it’s not privacy oriented at all, is from a municipal authority in Boston. Someone designed an app for them that would leverage the accelerometer in smartphones to identify potholes in the city roads. This was early on in the days of smartphones. The accelerometer is finely calibrated, and this functionality meant that when a person was driving along and drove over a pothole the accelerometer would register it, log where the pothole was, and communicate that to the municipal authority. They could then see where the potholes were around the city and prioritise their pothole filling crews. But what they very quickly found was that the distribution of potholes was not equal to the distribution of smartphones. The more affluent areas where people were more likely to own smartphones were generating far more data about the incidence of potholes and therefore commandeering those resources. AIs and other digital technology can exacerbate misallocation of resources.

Wide area location tracking

Use of digital technologies comes with a trade-off. If you want the functionality of Google maps the trade-off is that your location is being broadcast back to Google. This is helpful for the aggregate, and because you are participating in this system it means that everyone on the road is going to have really accurate information about how long it is going to take to get to Petone. What people often don’t realise about that transaction is that there is a repository of everywhere they have been. If I went out onto the street and asked someone, would you mind carrying a tracking device for me that is going to be monitored by a multinational company based in Palo Alto, most people would say, ‘No, get out of here, who do you think I am.’ Of course, they are doing this already. It is almost impossible to opt out of the tracking Android does. And I say almost impossible not because of dark patterning, which are tricks used in websites and apps that make you do things that you didn’t mean to, like buying or signing up for something, and which are expressly designed to make it difficult for people to opt out. It is impossible to opt out of the tracking that Android does because it is technologically impossible. You cannot switch it off; even if you turn off location you are still pinging against Bluetooth and Wi-Fi signals. You are still broadcasting your location with the telecommunications company and that is all being aggregated by Google. In April 2021 the Federal Court of Australia found that Google misled consumers about personal location data collected through Android mobile devices between January 2017 and December 2018, through ubiquitous location tracking. The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission Chair Rod Sims said, ‘Companies that collect information must explain their settings clearly and transparently so consumers are not misled. Consumers should not be kept in the dark when it comes to the collection of their personal location data.’*

* Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Google LLC (No 2) [2021] FCA 367; Google misled consumers about the collection and use of location data (2021, April 16). Retrieved from www.accc.gov.au/media-release/google-misled-consumers-about-the-collection-and-use-of-location-data

How are understandings of privacy changing?

Binary public/private concept of privacy

One of the real shifts that we have seen is a move away from a binary concept of privacy, being it is either private or it is not. The old common law concept is that if it is in the public domain then it cannot be private; if you are walking down the street you have no expectation of privacy. That has been reflected in our data protection laws, and the Privacy Act has a number of exceptions to the restrictions of information, including being publicly available information.

But some of the new technologies, such as biometrics, really challenge that. Is your face publicly available information just because you happen to be wearing it when you are out in the street? Is that enough to say that you no longer have any right or expectation that those very unique facial measurements that distinguish you from everybody else can’t be harvested and put to use for a range of benign or malign purposes? These are interesting questions.

This blurring of the binary boundary between public and private information has been recognised in a 2017 amendment to the Privacy Act, introduced by the Harmful Digital Communications Act. That amendment changed the ‘publicly available publication’ exception, to say publicly available information could be used unless ‘in the circumstances of the case, it would be unfair or unreasonable to use that information.’*

* S22 Privacy Act 2020, Information Privacy Principle 11, Limits on disclosure of personal information (1)(d).

Privacy as a public good

Another shift is this evolving, developing thinking of privacy as a public good. We have traditionally looked at privacy as something that is associated with individuals: your privacy is important to you, it is not important to me, my privacy is important to me. But the concept of privacy as a public good, as a precondition for enjoying the benefits of the digital economy, as a means of ensuring we develop our personalities more fully, is starting to be recognised more. And if there is a public good and not just a private good, then some public good kinds of interventions, such as a good privacy standard like a healthy food standard or a food hygiene standard, start to make more sense.

The NZ COVID Tracer app is a really good illustration of privacy as a public good. There is a social contract which says, ‘We need to work together to stamp this out.’ Part of that is that we are going to ask you to give up some privacy. We are going to give you an app and we are going to ask you to scan in everywhere you go, or sign a register everywhere you go, and we are going to socially shame you if you don’t. We are going to fulfil our end of that social contract by giving you a guarantee that your personal information is not going to be used for anything other than pandemic management. In Singapore they did that first part, and then 8 months after they rolled out their app they said, actually this would be really handy for law enforcement. I think that if we did something like that here that would be terribly undermining of the social contract that has contributed to the success of our pandemic management.

Māori and cultural approaches to privacy

Under the Privacy Act 2020 the Privacy Commissioner is explicitly required by law to take into account different cultural approaches to privacy. The Commissioner also, as part of government, has an obligation under the Treaty, and has to try and engage with Māori concepts. There is a fairly long history of Māori becoming frustrated at being the objects of study and as the net donors of data, and a concomitant movement towards greater data sovereignty and exercising kawanatanga over data of their people, on the basis that it is a taonga and they are entitled to exercise control over it. It is really important for us to engage with Māori over these issues.

The other issue is that privacy as a human right is based on a fairly ethnocentric conception of individual human rights rather than a more whānau or collective based system. I think our law is capable of accommodating both approaches but a basic unit in western society is the individual. A basic unit in Māori society might be whānau. And the law doesn’t recognise rights over groupings; it recognises individual rights. So there are some points of tension and areas where we need to reconcile, and I think there is plenty of elasticity in the law to do that. We are seeing organisations like Statistics New Zealand engaging more deeply with te ao Māori and recognising the need to not only have Māori input, but also to recognise Māori sovereignty over data.

Privacy in other jurisdictions

Other jurisdictions have their own approaches to regulating new digital technologies. We see this tension in the world where Europe has followed a precautionary principle. In GDPR there is a principle which says you shall not deploy any new technology without a mandatory Privacy Impact Assessment (EU 2016). The US approach is do whatever you like, and if it causes great harm later maybe legislators will step in once the horse has bolted. That can also be subject to litigation. I was staggered to find that the American Civil Liberties Union has sued states that have enacted revenge porn prohibitions because they are valuing freedom of expression over the very grave harm that those kinds of betrayals of trust cause.

We need international law on this, we need international conventions, and the people who say it is too hard are the ones in whose interest it is not to have a body of international law. There is a Council of Europe treaty called the Convention for the Protection of Individuals with regard to Automatic Processing of Personal Data, which has been ratified by all members of the Council of Europe, and is signed up to by all European countries. A number of non-Council of Europe states have acceded to the treaty, and New Zealand is an observer. It is broadly adjacent to the GDPR, and it could become an international standard. We do need some coordinated international law on this because otherwise we are net takers of technology that is imbued with values that may not be aligned with our own, for example, the fetishisation of the right to free expression as paramount over other rights such as privacy.

Role of IT professionals

I think it is important that we recognise that engineers and coders are really the architects of society, and we have to engage with the people who are building the technology or they will build stuff that we then have to live with, like it or not, and that may have implications. So privacy professionals have to have a closer relationship with the architects of the technology. An engineer’s instinct is to get you from A to B by the shortest possible route, not necessarily looking at the implications of taking that shortcut and seeing what’s missing from the more prevaricated route. The first Privacy Commissioner, Bruce Slane, used to say ‘Inefficiency can be very privacy protective.’ Doing things fast and efficiently without thinking about the implications is not necessarily going to result in a net social benefit.

Privacy by design is a really important tool for people who are writing code or designing technology to come back to first principles and to think through the implications of the problem they are trying to solve. What are the range of ways in which they can do that? What are the implications of those ways? How do you minimise the adverse impacts? There are choices at every point. A methodology like privacy by design can inform those choices in ways that we might not intuitively reach for if we just have an A to B mentality.

For example, the principle of data minimisation can be included in the process of designing use cases. At every point you should be examining what are you collecting, and why, what are you going to do with it, and how long are you going to keep it? If there is a data by-product of a process that you are developing and you do not address those questions up front someone will conceive of a use of that metadata later. That secondary use may not be in any way related to the bargain the consumer thought they were entering into when they accessed that service.

I get a bit of pushback sometimes and told to stick to my knitting when I criticise the actions of some of the social media companies, their business models, or the way that they maybe deplatform some people and not others, and people ask what has that got to do with privacy? The thing is that these are industries based on personal information, so everything they do has something to do with personal information. Their algorithms are pointing you in this direction, or in that direction; they are amplifying certain messages, based on what they think they know about you. So privacy is more and more ubiquitous as a consideration in society and in the economy. And it’s not going to slow down.

Trust

Trust is an essential core principle in the protection of personal information. When we give up personal information to the technology companies we make ourselves vulnerable. In our most intimate relationships we make ourselves vulnerable, that is a relationship of trust. When we expand that out to the everyday digital transactions that involve giving over a little bit of ourselves, which is our personal information, again it’s entrusting that person to treat it with respect, to keep it safe, to not abuse it. And if they do abuse it, or lose it, or not respect it, then that undermines the trust. It means we are less likely to engage with that service, or we might lose confidence in the platform, or in the technology altogether.

New technologies on the horizon

Data localisation

Internationally there is an interesting phenomenon that is developing that is data localisation. This is a regulatory requirement to maintain data within the source state’s jurisdiction. You might with the best intentions call Māori data sovereignty a data localisation movement, as it could be argued that Māori data shouldn’t be hosted on an AWS cloud in Sydney or in Europe. It can also be that data can be hosted in another country but it also has to be kept within jurisdiction so the government of that territory can have access to it. Russia has a data localisation rule and it is argued that any information there is prone to use by state security agencies.

The rule can also be co-opted by industry to extract economic rents from commodity storage. If you have a data localisation rule in an economy that has a limited number of IT participants then you can not choose to store your data on a rack in a country next door at 20% of the price; you are forced to make an uneconomic decision within the economy. Data localisation is a growing trend around the world as a reaction to the kind of NSA surveillance that Snowden exposed, but other motives exist, either state sponsored or as a local industry protectionism tool.

It also goes against what most industrialised nations want to achieve. The Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe hosted the 2019 G20 summit in Osaka, one of the key themes of which was ‘Data Free Flow with Trust’, an approach that attempts to allow the free flow of data under rules upon which all people can rely. This is an emerging tension that we are yet to see play out, what these kinds of artificial barriers to data movement are going to do to the world economy.

Open data, anonymization and differential privacy

One of the other threads is open data and the importance of data sets being available to industry, to lubricate the economy, to inform policy-making decisions. This comes with risks even if you anonymise, and one of the issues is re-identification. The more information you collect the more able you are to defeat attempts of de-identification. A good example is research by Culnane, Rubinstein, and Teague (2017): the Australian government decided to put online a dataset of 10% of their de-identified longitudinal medical billing records. The records were de-identified so they had the year of birth of the person, and their children if any whose birthdates were hashed by taking out the date and putting a date range of 28 days. The team used a linking attack on information from Wikipedia pages and online news stories about famous Australians who are also mothers to make 18 queries of the database; they found three unique matches. This then made it possible to link that person to their medical billing history.

There is a lot of work being done on differential privacy, how you get the benefit of these large datasets in ways that continue to respect privacy, so there is a lot of work being done to get the benefit of open data in a safe way. But the maths is hugely difficult.

Conclusion

To sum up, privacy is a very contextual subject. Just as technology is changing, society’s understanding and expectation of privacy is also changing. Since the Privacy Act 2020 came into force reported privacy breaches doubled in the first four months. It is not sufficient to work with personal data without considering privacy, and privacy by design is an important tool to identify privacy implications of the technology that we create. The Office of the Privacy Commissioner has a range of resources and tools available for free on their website for individuals, organisations, and for specific sectors.

, Privacy Commissioner, was appointed to the independent statutory position of Privacy Commissioner in February 2014. He is currently serving his second five year term. He provides independent comment on significant personal information policies and issues. Prior to his appointment, John practiced law in Wellington for over 20 years specialising in information law while representing a wide range of public and private sector clients. He has acted in legal roles for the Ministry of Health, State Services Commission, Department of Prime Minister & Cabinet and Inland Revenue Department. For 15 years, he held a warrant as a district inspector for mental health and has also been a district inspector for intellectual disability services.

, PhD, MIS, LLB, is a researcher in the Wellington School of Business and Government, specialising in privacy, digital government, data ethics and data sovereignty.

References

Culnane, C, Rubinstein, B & Teague, V (2017). Health data in an open world; A report on re-identifying patients in the MBS/PBS dataset and the implications for future releases of Australian Government Data. ArXiv. Retrieved from arxiv.org/abs/1712.05627

EU. Article 35 Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (GDPR) (2016). Retrieved from eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/o

OECD guidelines on the protection of privacy and transborder flows of personal data (1980). doi.org/10.1787/9789264196391-en

Warren, SD & Brandeis, LD (1890). The right to privacy. Harvard Law Review, 4(5), 193–220. doi.org/10.2307/1321160

Zimmerman, P (1995). PGP source code and internals. MIT Press