Hobbyist computing in 1980s New Zealand: Games and the popular reception of microcomputers

Personal computers were claiming that they could do anything, but actually they did nothing. With Famicom, we were the first ones to admit that our computer cannot do anything but play games.

Masayuki Uemura, Nintendo, 1986

So what did the home community do with these machines in the eighties? More than buying a cassette and playing a game. Actually, there’s no information. We had to go to eBay, buy old analog ZX Spectrum Basic books, and try to find out ourselves. And we made a DVD out of it, to have the experience back of just fiddling around on a computer.

Joan Heemskerk

If, as has been suggested, those born now are the first generation of ‘digital natives’, the children of the 1980s were the first generation to experience micro computing firsthand. Many Kiwis of this generation grew up having access to these machines: the TRS and System 80s, the Spectrums, and the Sega SC3000, to name a few popular makes. But it was not only the young who embraced these machines. Relatively cheap, low-end 8 bit machines were embraced by a wide cross-section of the population. For many it was their first taste of computing, and they were keen to learn.

Today, little attention is paid to what early microcomputer enthusiasts got up to. Perhaps because many were young, their pursuits have tended to be overlooked or dismissed as insignificant. Such a view is erroneous. The period and hobbyists’ activities are significant for a number of reasons. It is in the 1980s that we see users actively experimenting, playing around with computers and seeing what they can do. The experience of ‘fiddling around’ on computers provided valuable insights for users into computers’ requirements, breeding many programmers along the way. Users of this period consistently point out that unless you programmed a computer in the 1980s, it did nothing, and there was little point in owning a micro unless you programmed it yourself.

So what did people write? In the early 1980s, all sorts of claims were made for what microcomputers would be good for in the home. These included such ‘useful’ — though unlikely — tasks as recipe filing, the preparation of household budgets, and auto maintenance scheduling. Despite these suggestions, the major use of many micros was probably to play and write games. Games were highly effective at familiarising new users to the technology. They were relatively easy to write and the limited memory and processing power of the early micros meant that games were one of the things that computers were good for. Together with many of the other programs that hobbyists devised, games fit into a class of software that has been classed as ‘funware’, that is ‘non-industrial, non-professional, non-commercial, or non-academic [in] character’. The pleasure and fun that users derived from playing around with — and playing games on — computers probably partly accounts for the fact that it is in the 1980s that a popular culture begins to emerge around the use of microcomputers, by non-experts.

As part of an in-depth research project into the history of digital games in New Zealand in the 1980s, I interviewed people who were active in the microcomputer scene during this period. In this chapter I blend extracts from the first person accounts of Mark Sibly and Simon Armstrong, Fiona Beals, John Perry, Michael Davidson, and Neill Birss with a range of textual and archival sources. I focus on the beginnings of a New Zealand hobbyist computing culture, specifically the support mechanisms that encouraged those New Zealanders who were interested in learning how to use microcomputers. Largely informal, these include publications (books, magazines, and newsletters), the organisation of computer shows and user groups, and the computer use policies of computer-owning organisations (such as schools). In general, there is strong evidence of a ‘can do’ ethos existing across these activities and publications. The clear message was that anyone could use computers, and everyone should learn some code and ‘have a go’. While not everyone did, it’s my argument that these supports — many of which operated as gift economies — together with the experimental nature of computer use at this time contributed to what we might term the first generation of ‘microcomputing natives’: individuals who are completely at home with personal computing. Not all of my informants opted to cross from ‘enthusiastic amateur’ to ‘professional’ (though a number have careers in computing and IT), but all retain an understanding of what it is to program, and often, a facility to do so.

Books and other how-to guides

Many of my informants taught themselves to code, typically gleaning knowledge from exposure to a range of programs, people, and publications. Instructional publications (mainly books) were published in large numbers during the 1970s and ’80s. The range was partly due to the many different, incompatible microcomputers. Many books were written to introduce the student to BASIC (Beginners All-purpose Symbolic Instruction Code), and clearly intend for their readers to teach themselves to program. Most adopt an encouraging tone, as is evident in this excerpt from Inman et al’s TRS-80 guide (a Wiley self-teaching guide):

As a final note before you start, be aware that as you use this book, enter lines into your computer, answer Self-Test questions, and do the exercises:

YOU CANNOT DO ANYTHING WRONG!

There is no way you can ‘hurt’ or ‘harm’ the computer by what you type into it. You may make mistakes, but that is a natural part of learning and exploration. In fact, we introduce deliberate errors in several places as part of the learning process.

So, explore, enjoy, and tell us about your discoveries as you use your Radio Shack TRS-80 microcomputer.

Texts such as these were important sources of learning for many new users. Some were written explicitly for kids, some focused on a particular system, and some attempted to cover the most popular brands of computer. Growing up in remote Westport, with few chances to meet with other computer enthusiasts, Fiona Beals reported finding the Usborne range of books useful. With titles that include Craig Kubey’s The Winners’ Book of Video Games, Ian Graham’s Usborne Guide to Computer and Video Games, and James I Clark’s A Look Inside Video Games, Usborne’s titles appear to have prioritised the dissemination of knowledge and programs that could be used immediately, principally computer game code. Despite writing her own games and other programs from an early age, Beals recalls not knowing that ‘all those things were actually a computer language’, until she learnt BASIC in High School.

As well as showing users how to use simple commands, such books played an important demystifying role, debunking myths and reassuring users that they would not hurt or wreck the computer by pressing the wrong key. As Mendham writes, ‘Many films have shown computers exploding because of something typed in, and it is hard to persuade people that this simply does not happen.’ Often, in their attempts to demystify computers, these books use humour. Shayne Micchia, for instance, in his Pitman Press title The Bewildered Parent’s Guide to Computer Programming (distributed out of Wellington), not only uses a familiar style of cartoon illustration to make it more approachable and ‘fun’; he also devotes the first chapter to ‘Removing some misconceptions’. These include the fear of doing damage by pressing the wrong key, computers crashing, and the misconception that computers are smart and good at maths.

Many of these titles have the further goal of building confidence. For example, Ault writes, ‘It’s easy’ — ok, so the computer doesn’t speak English, you need to learn its language, but ‘computers can be easy and fun for just about everyone’. This claim — that programming is easy — is extremely common. It is extended to machine code in a free 16-page pamphlet entitled ‘Machine Code Made Easy’:

Add sparkle to your arcade action games, make your lasers zap aliens that no laser has zapped before, and utilise your utilities to their full potential. Make your aliens glide smoothly across your screen and make even the Spectrum appear to have real sound. Extend your machine’s Basic to do all the things you could ever want it to do. Oh, the joys of machine code!

‘Ah, but …’ we hear you say. ‘Isn’t machine code that difficult subject I read about in my manual?’ Well, yes it is, but it isn’t really all that hard, and with this series of cards, anyone will be able to get to grips with the subject.

Every popular home computer except the Dragon is covered fully in these cards, and very soon you’ll find yourself writing programs to rival anything you can buy. Well, fairly soon …

Beyond a mode of address that seeks to build users’ confidence, encouraging them that they, too, can write code, many of these instructional computer texts emphasise that programming is also a creative activity. ‘Computer programming is not an arcane art or even a mysterious science. It is a creative HUMAN activity’.

These references to fun and games require some contextualising. For hobbyists, using computers for recreation clearly provided enjoyment. This was not always understood by the computer business end of town. Some people in the computer business clearly did not get it. The article ‘Games People Play’ profiles computer executives from various companies in New Zealand, asking them about the games they play. While some own up to playing ‘Pacman’ or ‘Flight Simulator’, it is surprising how many admit that they ‘don’t play any games on the computer’. Comments range from ‘I don’t play games much but …’ to ‘… when I do, it’s with my 11-year-old son …’ to my favourite, from Peter Thompson of Data General:

Playing with computers in my free time is abhorrent to me — which is not the sort of thing I should admit when trying to sell computers. About two years ago I just about mastered ‘Pacman’, but these days I am more into fence posts and other rural things in my spare time.

The complete disconnect between the extremely supportive tone of the authors of the ‘how-to program’ guides and the lack of interest of people who are already in ‘the computer game’ (such as Thompson) in computer-generated fun is astonishing (and would, of course, change as a younger generation of computer enthusiasts moved into roles within the computer and software industries). The lack of levity in general is of concern to Mendham who, in 1986, asks, ‘Where on earth have all the computer games gone [in the workplace]?’ As computing has spread

into the commercial world … there has been a move to clean up its image. The humorous prompts, the Snoopy calendars and games which computer people so enjoyed have been shed in order to make things look more serious to the businessman with a cheque book.

Whilst Mendham concedes that first impressions do matter (and so having people playing computer games in the office would not do), too much emphasis has, he argues, been placed on productivity, in the process ignoring the value that play can yield, sometimes by stealth. He nominates games as valuable keyboard familiarisers as well as general computer confidence-builders.

Magazines

Magazines were a key source of information and support as well as of the all-important programs to enter. Many users were avid consumers of computer magazines, and subscribing to overseas titles was not uncommon. Michael Davidson, for instance, used to buy the UK-published Computer and Video Games, a magazine which:

was a huge influence on what games we liked and bought. C&VG also covered consoles and coinops as well as computers and it was from these magazines I first saw ads and articles about the more exotic systems and games. In th[o]se days the magazines and systems available were largely of a UK origin and the US scene had much less of an influence.

Several magazines were published locally. In this section I will focus on two that I have researched, Sega Computer and Bits and Bytes.

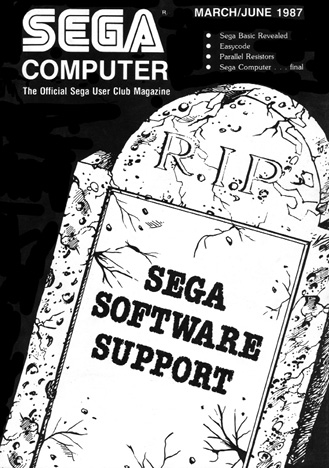

Sega Computer

Sega Computer makes an interesting case study, as it was set up by Grandstand Electronics, the distributor of the Sega SC3000 microcomputer, mainly to help them compete against Commodore. Being a North American computer, the Commodore had plenty of English-speaking software available. By contrast, the Japanese Sega SC3000 was distributed in very few other English-speaking countries and so lacked a software base. Setting up a magazine and a ‘club’ for users were shrewd marketing strategies employed to generate interest in the Sega line of products, and ultimately enable it to compete with Commodore — then the top selling computer worldwide — in New Zealand. Indeed, Grandstand managed to get the Sega range into Farmers ahead of Commodore and despite the latter being the leading computer worldwide in the home, more or less put them out of their Christmas business (personal communication, 5 November, 2006). A typed invitation from Grandstand Sales Manager, Phil Kenyon, to join the ‘club’ expounded the benefits users would derive in return for their $39.95 subscription fee: ‘owners’ were to receive the first six issues of ‘New Zealand’s first dedicated computer club magazine’, plus two free programs on cassette

Between 1984 and 1986, Grandstand put out around 10 issues of the magazine. By November 1984, they are touting Sega Computer as the ‘Official Sega User Club Magazine’. Magazine contents included: reviews; type in programs; letters; advertisements; and some articles on technical topics like random numbers, program languages, and machine code. Grandstand also promised to publish the dates and venues of anyone wishing to start a local user group. This decision probably partly accounted for the volume of Sega user groups that sprang up across the length and breadth of New Zealand: the August 1985 issue shows 14 Sega user groups, from Timaru to Tauranga.

While Grandstand may have begun the magazine to serve its commercial needs, the publication quite quickly took on its own significance in terms of the support it gave to the local community of computer owners. Users were invited (indeed expected) to contribute to magazines and it is clear that they did. Employing the language of clubs and membership, the magazine encouraged a participatory ethic. Phil Kenyon’s invitation in the first issue is representative:

This is your magazine, so we welcome your suggestions on what you want in it (no suggestions on where to put it if you please). Your support is needed to maintain the quality of the magazine, so come on all you budding superbrains — start sending in those programs and letters — all printed on your shining new Sega Plotter Printer, of course.

I look forward to hearing from you in the near future.

Programs were a key reason for buying a computer magazine in the 1980s. Renato Degiovani’s reflections on his period editing Brazilian magazine Micro Sistemas captures something of the energy and curiosity surrounding type-in software programs in magazines:

With issues that were quickly sold out in newsstands, it was eagerly read by users of personal computers, who looked for anything that would do something else with their computers and that they had not tried yet. The lists published were typed all night long, because this was the only fast way to obtain a computer program.

The editors were particularly keen for readers to contribute their programs, and they did. As well as publication, the ‘best’ submission in each issue would typically earn its author a small monetary ‘prize’. Having a program published in a magazine provided recognition for a user’s talents. Auckland teenager, John Perry, recalls that people were ‘pretty impressed’ when, at the age of 13, Grandstand opted to publish his game ‘City Lander’ on tape. This was not the first time he’d ‘made it’: Perry had previously had a program he’d written, ‘Harbour’, published in Computer Input. But this time round, Grandstand arranged a television spot on TVNZ’s Top Half as publicity for his achievements. Setting aside Grandstand’s clear self-interest in such instances, the company also spoke strongly in favour of locally written software, and in the time that they marketed the Sega system, they were a significant publisher of locally written software for the system. This, together with the ‘support’ that was often being mentioned, was evidently encouraging for a young community of hobbyist programmers. Readers’ appreciation — and criticisms — appear often in the letters pages. Sometimes, compliments are simply expressed in the form ‘P.S. Great magazine’, but the short letter from FK Maynard of Wellington sounds a common theme:

The article ‘Program Dissection’ in the September issue of Sega Computer is the most helpful we have read. We hope there will be many more such articles to follow. We look forward to receiving further issues of this magazine.

Maynard would receive another year’s worth of issues before Grandstand passed the magazine on when it began selling Amstrads. After that, Sega Computer (and the Sega club and club support) would be passed onto a series of others to edit and manage — first to Glenys Millington of Sega Software Support, then — when she in turn passed it on — to Poseidon Software. However, in a letter to subscribers, Poseidon claimed to have a ‘large amount of evidence that the magazine is being photocopied in numbers and resold’. This, together with low subscription numbers, led to their outsourcing publication to Michael J Hadrup. Hadrup took this on while he was a senior student in 1987, putting out roughly five issues — some of which were ‘doubles’ — before finally closing it down in 1988, in anticipation of the New Zealand launch of the Sega Master System.

Sega Computer was undoubtedly an important support for a nascent community and culture of Sega enthusiasts, and actual computer support was sold to purchasers as a key benefit of purchasing a Sega. The extent to which the Sega Users Club was actually a ‘club’ remains an open question. For Grandstand, the main aim of the magazine — and its publishing of software —was always to generate interest around the Sega in order to move more stock. The Sega was a product to sell, much like any other. But to say that a club ethic was not uppermost in Grandstand’s mind is not to say that users did not enjoy aspects of the club experience. As well as being an extremely effective strategy for creating a buzz around their product, the publishing of user group contacts in the magazine nurtured a following amongst Sega owners, supporting users in physically getting together, something I’ll discuss in more detail in the next section.

Bits and Bytes

Working as a journalist at The Press, Neill Birss was also looking for a part-time business opportunity. He had become interested in computers after purchasing Dick Smith’s version of the TRS-80, the System 80. Birss belonged to the TRS-80 club, which met in St John’s church hall in Christchurch. Noting the expense of overseas computing magazines, he thought he might try publishing a local computing magazine. Paul Crooks, a student and Treasurer of the Student Union at Canterbury University, had the same idea, and together they launched Bits and Bytes. The first issue came out in September 1982. At first they put it together using student publishing facilities at the university, where, Birss recalls,

the typesetting gear didn’t have all the symbols that were used in computer code, so we used to have to go along manually putting the tops on the I’s, etc. It was terribly amateur but the folk didn’t really mind. They were more concerned if it was wrong.

Despite these humble beginnings, the magazine grew, with subscriptions reaching ‘4–5000 quite quickly’. Birss notes: ‘It was quite successful. The big problem was never subscribers, it was the advertising, organising the ads.’

The magazine was pitched at home users, gamers, and small business users. These different audiences didn’t always sit easily together, as Birss explained to me:

We hired a local Christchurch cartoonist to do the covers, but he was exceedingly savage in his depiction of accountants. I actually liked them but my partner, Paul Crooks, didn’t. He was in charge of the ads; he was selling advertising. For example we had an edition where we tried to get accountants to advertise — because they were amongst the early users — but his depiction of accountants as hawks … well they wouldn’t advertise again. So we got rid of him after two or three issues.

There was, Birss observed, an ‘iron wall’ between ‘serious’ software people — that is, those who developed for mainframes and business — and the gamers.

A lot of the early computer people didn’t want to get involved — they were frightened of being associated with a magazine that was involved with games. They thought that in the eyes of the business market that might taint theirs as a games machine, because that’s where they all wanted to go.

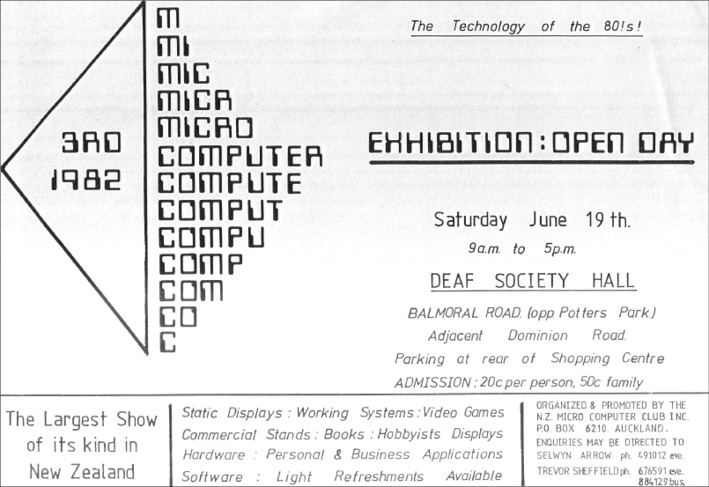

3rd Microcomputer Exhibition: Open Day, in June 1982.

Such fears of diminished credibility on the part of business no doubt responded to and fed off the often negative media coverage of digital games — particularly in ‘spacies’ arcades — in the period.

Like Sega Computer, Bits and Bytes would print programs in both Basic and machine code in the magazines, and encourage users to contribute their own programs.

That was one of the problems, I guess. There were so many brands of computers, all not compatible with each other … And people had to know commands like Peek and Poke, and they were actually putting things into memory cells … But the kids picked it up very quickly, and I think it was a very good — a great — introducer to technology. It was much more hands on, and I think in some ways more educational than the later stuff, well, as far as the technology side went.

Computer shows

Programming these early micros may have been a ‘wee bit more difficult to grasp’ than computing is nowadays, but as Birss tells it, there was no shortage of enthusiasts. Certainly, the computer shows and fairs that he and his partners staged as an adjunct to publishing Bits and Bytes were well attended.

Birss recalls putting shows on in Christchurch, Auckland, Palmerston North and Wellington. In 1983, the Christchurch Computer Show was held at the Christchurch Town Hall complex, over Friday and Saturday December 2 and 3. The catalogue and list of exhibitors was 12 pages long. Birss recalls that parents would often come along with their kids. Davidson attended ‘a large Computer Show in Palmerston North’ around this time, at which he saw the locally-made Fountain games console. The renowned collector of early New Zealand-made games recalls his first impressions of this:

to be brutally honest I thought it SUCKED compared to the other systems on display (Commodore Vic20, Apple II, Atari 8 Bit, Sinclair) and the only thing going for it was the free badges and stickers they were giving away on the Fountain stall …

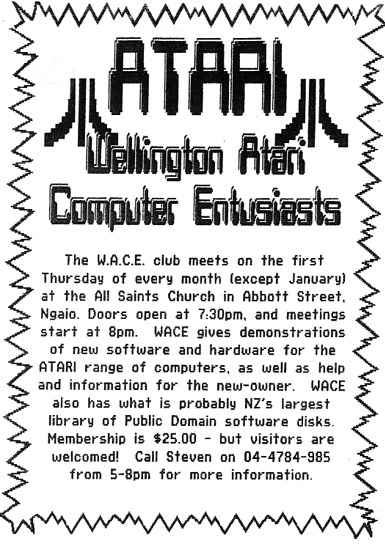

User groups

Both Sega Computer and Bits and Bytes included extensive User Group contacts in each issue. User group names typically provided two pieces of information: 1) where members congregated, and 2) the types of systems they used (e.g. Southland Commodore User Group). What they don’t convey is the level of enthusiasm these groups typically exuded in their early phases, when ‘it’s driven by the folk themselves’ who have that ‘let’s hire a hall somewhere’ momentum.

User Groups involved getting together with like-minded others, to share know-how and resources, in the tradition of other early technical hobbyist clubs (e.g. ham radio, meccano). Typically run fairly informally, the groups provided a social context for computing. They were one of the first times that people got together socially around, and because of, personal computers. In his writing on user groups for the Dick Smith VZ computer, Bob Kitch sees the shift from tinkering around with a computer to forming a user group as a natural development:

Users and owners … naturally tended to band together, to chew over mutual interests and problems … [Well, that, and the poor support they received from Dick Smith Electronics, according to Kitch.] These ‘jam’ sessions were most often held over the phone, but have you ever tried to satisfactorily discuss a software problem over the phone? The next stage was to organize a meeting of interested enthusiasts, usually on a weekend, in someone’s home or at a conveniently located hall. And so began a VZ USER GROUP.

When asked to name his best memory of the Sega SC-3000 era, Robert B Brian (author of the Sega Programming Manual and numerous Grandstand programs) nominates a user group meeting: ‘One of the very first meetings of the Wellington Sega User Club was held in my flat in Adelaide Road. I think meeting other users and sharing ideas, Software, FAQ etc was great’.

Some user groups published newsletters. As Kitch writes: ‘a fairly natural activity to flow from [the user group] is the production of a newsletter, to serve far-flung enthusiasts … and to record discoveries (be they hardware tricks or new programs) for other Users’. The quality of these varied, from those that were close to magazines of the era, to those that were handwritten and intentionally hokey. Regular columns with tutorials, tips, and program reviews were common inclusions.

Some user groups were active in software copying. Birss notes of his local TRS-80 club: ‘We’d all put in and buy one game from America and we’d copy it and distribute it around’. But while some were ‘copyfests’, the user group gift economy was multifaceted. It included the sharing of information and knowledge on topics such as RSI and ergonomic furniture. Some groups lent books and magazines to members, while others — such as the New Zealand Microcomputer Club — had ‘a large library of public domain software … available’. This group also participated in an exchange of newsletters back and forth across the Tasman and further afield. It also published a newsletter, ‘New Zealand MICRO’, which appeared inside local magazines. The Combined Microcomputer Users Group was an earlier, meta-group which, for a time, represented all of the Auckland clubs and groups. Formed in January 1982, it lasted just over a year, but during that time, the Group managed to design and manufacture low cost acoustic modems, which were the ‘main means of communication until low cost commercial modems became available in 1984’.

Wellington Atari Computer Enthusiasts (WACE) flyer.

It’s fair to say that not everyone found user groups an indispensable part of the early micro-computing landscape. Interviewing the early Commodore (and then Amiga) enthusiasts Mark Sibly and Simon Armstrong, I asked if there was a big local scene of Commodore user groups in Auckland where they lived. They reported attending only a few meetings, finding them ‘too much like church’. Simon explained: ‘the user group would be at the back doing piracy, copying discs, and the main people who were worshipping the thing stood up the front and talked about all sorts of crap.’ As young budding programmers, they spent more time ‘at home or at friends’ houses, learning how to program and making little games, experimenting with them.’ Sibly and Armstrong, who self-published their own games whilst at school in the 1980s (‘Dinky Kong’ was one such title), would go on to publish major game titles in the 1990s under the Acid Software name, amongst them ‘Roadkill’ and ‘Super Skidmarks’.

Schools

In this final section, I discuss the school computer room, as these were often sites or hubs where knowledge and programming skills were gleaned and honed. I asked Armstrong and Sibly whether there was a particular computer teacher at their school who encouraged or inspired them with their developing programming skills.

Mark: We had a computer teacher, but he was never very enthusiastic about the subject, and we sort of worked out our own stuff and just ignored him kind of thing. And he let us do that to a large extent.

Simon: I admired him because he was my brother’s teacher and he was the one who just let them [the computers] go at the weekends. I think he understood that with a book you can, if you want to, you can find out all you need to know about them.

Mark: We didn’t actually take computers at school til the sixth form — we weren’t allowed to, I think. We were using them from the third form, and I think by that stage we were way ahead of the teachers.

They did, however, spend time hanging out in the computer room, and ‘whenever you’d find something else out, it’d be easy enough to explain to every else’. Mark continues:

There was a very strong community aspect … and you could go there after school, and book out computers at lunchtime kind of thing. We used to go there and hang out and, you know, people would … after school would be quite intense programming sort of time. You learnt a lot there.

It was not only the presence of computers in a designated room or the sharing of know-how that was valuable; also significant were the flexible policies of schools on the use of their computers. Many allowed students to borrow the school’s computers on weekends and holidays, a level of accessibility that today seems extraordinary. Armstrong and Sibly were students at Auckland’s Selwyn College where, Armstrong recalls,

… they had Apple II computers in their computer room, way back in 85 or 86. They let us take them home on the weekends. You could book them out. That was pretty amazing: personal computers had just arrived and we were allowed to take them home. So my big brother — even before I got to high school — was bringing them home.

Michael Davidson — whose family owned a ZX81 — also enjoyed having the use of an Apple II system for a summer. His father had managed to borrow it from the local high school. As he notes:

At this time outside of Schools/Educational Institutes, very few people owned Apple systems privately as they were very expensive to buy.

We started off with just one box of games on disk and via a succession of friends who knew other friends we entered the wonderful world of Apple II piracy.

The beginnings of New Zealand’s hobbyist computing culture were somewhat haphazard. The supports I have been discussing — from books and pamphlets to communities of practice — were, for the most part, informal and incidental to the ‘serious’ business of computing in the 1980s. Initiated by entrepreneurs such as Birss and the Kenyons, publishing houses sensing a new market niche, and helped along by institutions of education, peers and community-minded people who were prepared to share their knowledge and skills with others, micro-enthusiasts were provided a climate in which they could absorb and experiment with these new toys. Games and play were close to the hearts of these ‘micro-natives’, as I’ve dubbed them: games were the programs they keyed into their computers; games were what inspired them and what they swapped; and unsurprisingly, games were what they wrote. Their developing adeptness as programmers occurred despite the ‘iron wall’ that existed between ‘serious’ software people and gamers, and the low esteem in which games were held by wider society at the time.

References

Anonymous (1984). Sega’s young programmers. Sega Computer, 21

Anonymous (1988, December 1987 — January). Games people play. Bits & Bytes, 28–29

Arrow, S (1985). Personal computers. In WR Williams (Ed), Looking back tomorrow: Reflections on twenty-five years of computers in New Zealand (pp. 105–119). Wellington: New Zealand Computer Society

Auckland Central Library (1982). 3rd microcomputer exhibition. Auckland: Auckland Central Library (NZ) Eph: Technology

Auckland Central Library (c. 1980s). Machine code made easy. Auckland: Auckland Central Library (NZ) Eph: Technology

Ault, R (1983). BASIC programming for kids: BASIC programming on personal computers by Apple, Atari, Commodore, Radio Shack, Texas Instruments, Timex Sinclair. Boston: Houghton Mifflin

Clark, JI (1985). A look inside video games. London: Usborne

Deane, J & Deane, J (1980). Easy way to programming in BASIC using the system 80 computer (1st ed). Sydney: Dick Smith Eletronics Pty Ltd

Degiovani, R (2003). Domestic pioneers Game Brasilis. Sao Paulo: Senac, unpaginated

Derkenne, M & McKinnon, B (1986). BASIC for the Microbee. Waitara: NSW: Honeysoft

Graham, I (1982). Usborne guide to computer and video games. London: Usborne

Haring, K (2006). Ham Radio’s technical culture. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press

Inman, D, Zamora, R & Albrecht, B (1981). More TRS-80 BASIC. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc

Jornmark, J, Axelsson, A-S & Ernkvist, M (2005). Wherever hardware, there’ll be games: The evolution of hardware and shifting industrial leadership in the games industry. Paper presented at the DiGRA 2005 Conference

Kenyon, P (1984, August). Welcome to the Sega users club. Sega Computer, 1

Kitch, B (n.d.). A history of VZ users groups in Australia and New Zealand. Retrieved 3 August 2004, from homepage.powerup.com.au/~intertek/VZ200/vz.htm (Site since removed)

Kubey, C (1982). The winners’ book of video games. London: Usborne

Maynard, FK (1985, January/February). Letter. Sega Computer, 2

Mendham, T (1986, 24 February). All work and no play in the office is bad for business, The Sydney Morning Herald, p. 14

Micchia, S (1985). The bewildered parent’s guide to computer programming. Melbourne: Ptman Press

Mr Judkins & Davidson, M (2002). NZ Game collectors. Retrieved 16 April 2010, from homepages.paradise.net.nz/nzgc/html/FeaturedArticles-MDInterv.html

Prensky, M (2001). Digital natives, digital immigrants. On the Horizon, 9(5), 1–6

Rackham, M (2010, 27 March). [Fwd: CALL FOR PROPOSALS Funware Shared Artist in Residence]

Rowlands, G (1978, 9 January). It’s an era of friendly little computers… The Sydney Morning Herald, p. 8

Saarikoski, P & Suominen, J (2009). Computer hobbyists and the gaming industry in Finland. IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, 31(3), 20–33

Sega Computer (1987). RIP Sega software support. Sega Computer, Magazine cover

Street, CA (1983). Information handling for the ZX spectrum. Maidenhead, UK: McGraw-Hill

Swalwell, M (2003). Multi-player computer gaming: ‘Better than playing (PC games) with yourself’. Reconstruction, an interdisciplinary cultural studies community, 3(4)

—— (2008). 1980s home coding: The art of amateur programming. In S Brennan & S Ballard (Eds), Aoteroa Digital Arts Reader (pp. 193–201). Auckland: Clouds/ADA

—— (2009). LAN gaming groups: Snapshots from an Australasian case study 1999–2008. In L JHjorth & D Chan (Eds), Gaming cultures and place in the Asia-Pacific region (pp. 117–140). New York: Routledge

Variable Media Network (2004). Echoes of art: Emulation as a preservation strategy [Symposium transcript]. Retrieved 6 April 2009, from www.variablemedia.net/e/echoes/morn_text.htm#contemp

Wellingon Atari Computer Enthusiasts (1991): Alexander Turnbull Library (NZ) Eph B: Computer

Wheeler, A & Brian, RB (2008). Sega SC-3000 survivors. Retrieved 16 April 2010, from www.sc-3000.com/index.php/An-interview-with-Brian-Brown.html

Wheeler, A & Davidson, M (2008, 30 June). SC3K tape software list. Retrieved 18 April 2010, from homepages.ihug.co.nz/~atari/SC3K08.html

Gameography

City Lander (1984) [Game]: Grandstand

Dinky Kong (1984) [Game]: Perspective Software

Roadkill (1994) [Game]: Acid Software

Super Skidmarks (1995) [Game]: Acid Software

Illustrations

Sega Computer Magazine Cover reproduced with permission of ex-directors of Nomac publishing

3rd Microcomputer exhibition: Open Day poster reproduced with permission of the New Zealand Computer Club (formerly New Zealand Microcomputer Club)

WACE flyer reproduced with permission of Bob McDavitt (ex-WACE committee member)