Making New Zealand’s cities smarter

The term ‘smart city’, originally referred to the use of technology to improve the lives of city citizens. It is generally thought to have been initiated around the mid-1990s by IBM and Cisco. In 1998, Amsterdam created what was called a virtual digital city (De Digitale Stad) initially to promote internet usage.

Some credit Bill Clinton* with giving the term a real kick-start when in 2005 he used his philanthropic organisation, the Clinton Foundation, to challenge Cisco to use its technology capability to improve city sustainability. Cisco subsequently invested $US25 million over five years working with cities such as Amsterdam, San Francisco and Seoul, on pilot urban technology projects.

* Falk T. ZDNet (2012). ‘The origins of smart city technology.’ zdnet.com/article/the-origins-of-smart-city-technology/

A literature review of 200 publications in August 2020 determined there were three core elements to the definition of a smart city (Stübinger & Schneider 2020):

- The target group is a city or urban community

- The way of living and/or working within the location is enhanced

- Information and communication technologies are employed

Over the last ten years its definition has widened to incorporate a wide range of what are termed ‘smart’ strategies and tools for improving city operation and life.

‘Smart city’ has come in for some criticism over the years as some city leaders have seen it as a term promoted by technology vendors and consultants. Worries around data privacy and surveillance tracking, pre-COVID-19, have also stymied some smart city progress. In other cities, inadequate technology infrastructure has been a constraint. Despite this, thousands of cities around the world have adopted smart city plans or approaches contributing to a multi-billion dollar industry.*

* Intrado. Research and Markets (2020, Oct). Smart Cities Market Report 2020. globenewswire.com/news-release/2020/10/05/2103315/0/en/Smart-Cities-Market-Report-2020-Global-Forecast-to-2025-Market-Size-is-Expected-to-Grow-from-410-8-Billion-in-2020-to-820-7-Billion.html

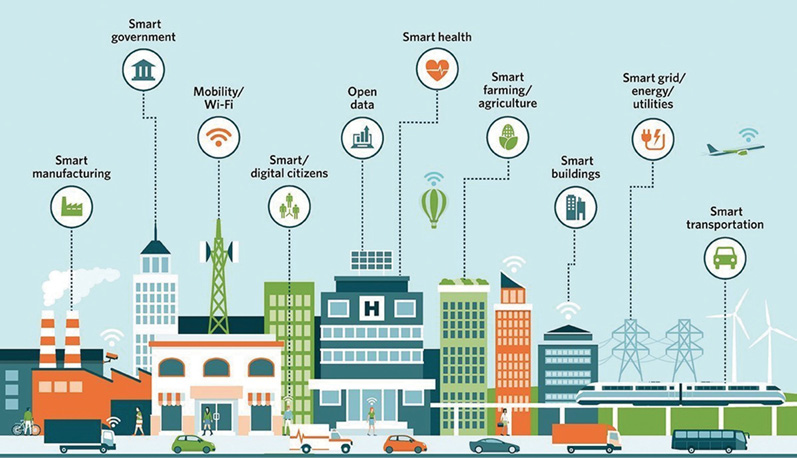

Figure 1: Smart city components.

TechTarget 2020

Although core city services and operations functions were an early smart cities’ focus (e.g. energy, transport, waste, water), as urban challenges have increased this focus has expanded to include the community, cultural, economic and social infrastructure including agriculture, education, safety and health as shown in Figure 1.

Smart cities have been a significant growth industry around the world, and in 2019 were valued at $USD83.9 billion. Before COVID-19, their value was expected to grow at an annual compound growth rate of nearly 25%.*

* GrandViewResearch (2020). Smart Cities Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report. grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/smart-cities-market

In 2007, for the first time in history the global urban population exceeded the global rural population. In New Zealand, the percentage of urbanised inhabitants reached 86% in 2018.

The smart cities industry growth has been spurred both by developments in technology and also by a drive to help solve the environmental, housing, transport and other problems stemming from urban population growth.

The ability to capture and better analyse data has been an important consequence of technology development as this has allowed cities to acquire a much greater range of data, become better informed and as a result improve city decision making. Some of the tools used to achieve this include:*

* Land Information New Zealand (2016). Smart Cities Strategic Assessment. linz.govt.nz/about-linz/what-were-doing/projects/previous-projects/smart-cities

- The development of low-cost and low-powered system-on-a-chip (SOC) processors which can be integrated into cost-effective sensor networks.

- Sensors, whose fall in cost and power consumption has meant they can be deployed in urban environments and across relatively wide geographical areas linked using wireless mesh networks.

- Expanded cloud-based processing has meant that data can be collated from a wide range of disparate sensors and networks using a cost-effective mechanism available to a broad range of users and across different technical interfaces. This has also facilitated an open platform on which applications and solutions can be developed.

- Big data analytics which use powerful statistical tools and predictive algorithms and can provide insights previously unobtainable from conventional analysis.

This introduction of sensors, ‘internet of things’* (IoT) applications, big data analysis and systems interconnection has been at the heart of much smart city activity growth.

* IoT has physical devices (the ‘things’) linked to an internet-enabled network so they can communicate and exchange data between each other without human involvement.

The New Zealand context

Over the last ten years, New Zealand’s growing smart cities capability has involved technology being deployed in new ways mainly in city environments to improve services, but being a smart city means so much more than just using technology well.

Wellington recognised the role a smart city could play in helping the city achieve its objectives when it published its ‘Towards 2040: Smart Capital Plan’ in June 2011. The Christchurch Central Recovery Plan published in 2012 also highlighted the role of smart technologies. In both cases, the documents focused on a broad definition of what a smart city could achieve. Wellington referred to the role social infrastructure could play in building a healthy community, how information is used and what skill levels the population have. The Christchurch Plan also talked about the importance of social infrastructure and designing the new city in a way that kept options open for future smart services.

In 2016, Auckland Council’s Chief of Strategy said the most important element in a smart cities approach was to have citizens and other key city stakeholders embedded at the centre of all that the council did.*

* Auckland Council (2016). ‘Auckland Conversations: Smart City — The Vision for Auckland.’ conversations.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/events/smart-city-vision-auckland

The key opportunity being considered by these and some other New Zealand cities, was how they could use technologies to improve but also measure in real-time the economic, environmental and social health of a city, and in doing so help to ease the growing housing, congestion and environmental pressures. International experience indicated the technologies could also be used to improve city services and asset management by producing, analysing and reporting real-time information and trends, with resulting improvements to city operations.

Cities have added sensors on pavements, rubbish bins and streetlights to allow, for example, rubbish bins to be emptied more efficiently and street lighting to be adjusted as light levels change. Consequently, there have been operations and energy savings and the resulting data analytics are proving valuable for local authority operations and investment decision making.

In city transport, IoT technologies are being used to better monitor essential infrastructure, improve network safety, react more quickly to congestion, and provide real-time data to enhance route planning.

By 2015, a range of smart cities projects were underway in New Zealand cities. Land Information New Zealand (LINZ) together with funding from the Treasury, set-up the Smart Cities Evaluation Programme.* It assessed the effectiveness of thirteen smart cities projects utilising sensing technology and real-time monitoring, underway in Auckland, Wellington and Christchurch.

* Land Information New Zealand. ‘Evaluation of the Smart Cities Programme (2015–2016)’. linz.govt.nz/about-linz/what-were-doing/projects/previous-projects/smart-cities

The research objectives were based on the Treasury’s Living Standards Framework, which aimed to boost the wellbeing of New Zealanders through better and safer use of data, encouraging innovative infrastructure investment practices and greater agency collaboration.

The smart city projects (which are covered in detail in the next section), were found to have delivered ‘efficient and effective smart sensing systems’ and they captured and processed data which, when combined with good analytics, helped inform decision making. Data visualisation tools which were also used by some projects were beginning to produce comprehensible, real-time data. This included data for air quality, pedestrian and traffic movements and water quality. The evaluation programme concluded that a more accurate view of city operations was now possible as the data helped to build a better understanding of how citizens interact within their urban environment. This could then be used to direct local authority funding more effectively.

By the end of 2016 LINZ had concluded that smart city technologies had the potential to produce significant societal, environmental and economic benefits for towns, cities and communities.

At this point, a key opportunity in New Zealand’s smart cities progress was missed. The LINZ report concluded that the learnings from the programme should be widely shared with local and central government, and the private and not-for-profit sectors. It also recommended a central government ‘home’ be established for the ownership and oversight of a NZ Inc., smart cities programme. The programme would be driven by cities, but with strategic coordination and support from a government agency. Many cities could have undertaken the same smart projects regularly, using the same vendor, so greater coordination would be valuable. However, some had misgivings about this approach and neither of these important recommendations were progressed.

Two years earlier Singapore initiated its Smart Nation strategy, establishing a S$2.4 billion programme to link infrastructure, software and services, to improve public transport, state housing, local amenities, other infrastructure and public services. This coordinated effort has produced a comprehensive strategic plan for the island nation, contributing to its high labour productivity and per capita income, and has meant Singapore regularly leads global smart cities rankings.*

* Poon King Wang. CNA (2020, January). ‘The revival of the digital economy.’ channelnewsasia.com/news/commentary/singapore-smart-nation-city-digital-economy-government-success-12295302

Despite the lack of a coordinated approach, individual city progress has been made in New Zealand. Several cities have started to feature regularly in the prestigious IDC Smart City Asia/Pacific Awards (SCAPA). The SCAPA were established in 2015 to identify leading smart solutions being developed in response to challenges cities were experiencing. Some of this progress will be outlined in the next sections.

As SCAPA indicates, within New Zealand, Christchurch and Wellington have taken the lead with smart city strategic approaches. Auckland, Hamilton, Palmerston North, Queenstown and other towns have also increasingly used a range of new technology tools and smart city practices.

Christchurch

The Christchurch earthquakes in 2010 and 2011 provided an opportunity for New Zealand’s second largest city to start anew and deploy smart technology at the heart of the extensive rebuild. As part of the rebuild planning, the Sensing City project* was advanced by the government in 2013. The project was billed as world leading and its objective was to transform Christchurch into a smart city of the future.** An intelligent infrastructure network was planned to include a sensor array which would monitor air pollution, pedestrian, traffic and water flows.

* ‘World-first Sensing City project launched’, Arup, 2013

** ‘Callaghan backs Christchurch as Sensing City’, NZ Government, 2013

Unfortunately, in less than two years the project was pulled. It just did not get the traction needed from the controlling authority, the Canterbury Earthquake Authority, which was grappling with competing priorities. Their priority was to restore the basic services lost in the earthquake rather than the more future-focused Sensing City. One positive outcome, however, was that the air quality component of the project was retained and delivered. The original project also showed the direction for other smart opportunities and in 2015 Christchurch City Council formally launched its smart cities programme.* The Smart Christchurch site** got underway in 2016.

* Teresa McCallum was Christchurch’s Smart Cities Manager 2016–19. Michael Healy has held the role since August 2019.

** Christchurch City Council n.d. ‘Smart Christchurch.’

The previously mentioned LINZ evaluation reviewed a series of Christchurch smart city projects at the end of 2016. These were:

Transport

- Smart Parking: this project sought to piggyback off learnings and systems recently operationalised in Wellington. Testing of sensors has been completed, with the demonstration unit ready to be displayed to wider stakeholders.

- Pedestrian zones: KITES* and Wi-Fi sensors were installed in pedestrian zones in central Christchurch to provide better and real-time information about pedestrian movements.

* KITE is an NEC sensing platform allowing a city to implement sensors in any location to gather data.

Both projects had links to and worked off similar Wellington City Council activity.

Environment

- Air quality: KITE platform sensors collect very good quality data on Christchurch’s air quality to improve the understanding and city response to air quality issues including particle presence.

- City services: The Open City Verticals Smart City Block project aims to disaggregate vertical city services (drainage, parking, street lighting and waste management) enabling a focus in investment projects rather than a single-use-case

- Rubbish: the project looked at installing rubbish bin collection sensors and also at the possibility of compression units in high-use rubbish areas.

- Street lighting: sensors were installed in streetlights to allow the lights to be automatically turned off and to evaluate the optimum light brightness — providing energy and operational savings.

- Water: A water monitoring system provided a visualisation tool and a model of areas prone to flooding to improve flood prevention responses — which the public could access.

Leveraging the Wellington City Council’s Smart Cities Backbone (a common operating platform), the council installed a Christchurch Backbone with KITE data points integrated into one system. A series of other KITE sensors were installed in the city to expand and improve the monitoring of air temperature, barometric pressure, carbon dioxide, lighting and noise levels, creating an overarching flexible sensing platform.

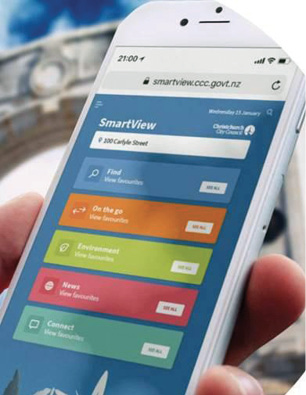

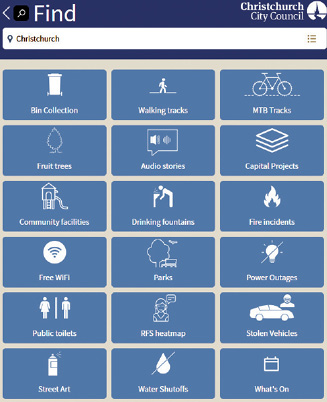

This foundation smart project work in Christchurch culminated in the development and launch of SmartView (Figure 2) in early 2018. This comprehensive web-based application gives users access to a wide range of real-time information about Christchurch leveraging the earlier transport and environmental smart activity already in place.

Figure 2: Smartview.

Smart Christchurch 2018

It aggregates data from different public and private organisations to provide information on car park availability, community consultations underway, electrical vehicle charging stations, roadworks, street art information, transport options and more. It was created with the vision that it could be replicated around the country to form a SmartView NZ.

Figure 3: The EQRNet control device.

Christchurch City Council 2018

EQRNet (Figure 3), launched in July 2018, is a network of 150 sensors installed at council facilities and at some traffic signals which provide essential real-time ground movement information for building owners, tenants and other stakeholders. It provided a much greater level of information than the existing GEONet system. In 2020, Christchurch won the Public-Safety-Disaster Response/Emergency Management category for EQRNet at the IDC Smart Cities Asia-Pacific Awards.

The city has also used 3D models of the CBD for visualisations of before and after the earthquakes to help with consultation and assist it to create a digital twin to aid planning.

Smart technology has also been used to detect water pressure fluctuations to protect against damage to the city’s water network. A more significant investment in water pressure, acoustic sensors and smart water-flow meters, is under consideration as part of enhanced management of fresh, storm and wastewater.

In 2020 Christchurch began a process of updating their smart cities strategy to ensure it was driven by a strong community-first approach responding to key local issues and providing adequate information so citizens could be informed of progress.

Wellington

In 2011, Wellington City Council published Towards 2040: Smart Capital. The report focused on making the best use of knowledge, investments and technology, to deliver a more diverse and resilient economy for the city (Wellington City Council 2011).

Wellington has operated its Smart Wellington programme for a number of years. This brings together a range of citizen, private, non-government organisations and government agencies. The focus is not just on the technical developments needed for the city but also on engagement and community and business sector involvement.

The programme uses a wide range of technologies such as, embedded sensing capabilities, IoT capability, machine learning and virtual reality, to manage connections between residents, manage resources and oversee traffic movement. The objective is to use both partnerships and technologies to create a better environment within the city, improve the city’s social systems and make the city more resilient in order to improve recovery from civil emergency events such as the 2016 Kaikoura earthquake.

As a result, the Smart Wellington programme has helped the city better understand urban change and more effectively respond to challenges and opportunities.

The Wellington City Council developed a commercial partnership with Japanese information technology and electronics company NEC in 2014. Together with their partners they developed a range of initiatives including:

- civic hacking communities to create new citizen made apps, websites and services using city data.

- an IoT backbone making installation of sensors simple, inexpensive and from any provider or maker.

- an inter-agency platform facilitating co-operation across the social and community agencies in the city.

- machine learning and advanced analytic processing to create further insight into city issues.

- virtual reality engagement platforms used to make data accessible, useful and understandable.

The NEC partnership, which concluded in August 2018, helped establish a camera and sensor network to respond to antisocial street activity, better manage graffiti and control pedestrian traffic flows. The CCTV behavioural analytics platform pilot, which examined whether it was possible to identify begging or potential on-street violence, did not continue due to mixed results. However, other elements of the network were retained to assist the city manage peak-event flows at the ASB Sports centre and the Wellington railway station.

A core objective of the design of Smart Wellington has been to create these systems to be as modular, scalable and open as possible to adapt to the growth and development needs of the city. This flexibility has made the installation of additional sensors straightforward and inexpensive and also facilitated inter-agency co-operation across the platform.

The Smart Wellington programme was included in the Digital Government Showcase which was part of Digital 5 2018 which met in New Zealand. Digital 5 (D5) is a collaborative network of self-identified leading world digital governments.*

* New Zealand was one of the founding members of the Digital 5 group in 2014. It is now referred to as Digital Nations with the addition of five further members

The LINZ Smart Cities Programme information evaluated the three key Wellington achievements:

- The Wellington Smart Cities Backbone, otherwise known as a Cloud City Operations Centre,* which provides the dashboard system on which the KITE data is displayed

* The CCOC is the analytical aggregation tool allowing sensors to send valid data back to a central hub.

- The Flexible Sensing Platform which allows a range of different sensors to be brought together into a sensor ‘hub’. Sensors have been rolled out to key activity zones including Courtney Place, Cuba Mall, Manners Mall and the Wellington Railway Station.

- Transport and Pedestrian Counting: this multimodal project uses CCTV cameras to provide key data and analytics on pedestrian activity.

Specific smart projects the city has developed include deploying IoT capability across the sensing platform to better understand earthquake impact on building performance. Machine learning has contributed to the council’s management of endangered birds and enabled them to have a better grasp of anti-social street behaviour.

Virtual reality (VR) engagement platforms have also been used to boost citizen awareness. In 2018, the council developed a simulator to show residents what impact rising sea levels could have on city streets.

Utilising VR has been an important part of Wellington’s development of its leading digital twin programme* which is informing city infrastructure and civil defence planning. Digital twinning has been used in the design of both a new call centre and a library — improving the efficiency of the engagement, boosting equity and reducing regulatory time and cost.**

* Build media (2020). buildmedia.com/work/wellington-digital-twin

** My Smart Community (2019 August). mysmart.community/2019/08/19/scp-e124/

Another strategy has been to encourage citizens to develop their own apps to aid the city. The council has been an active supporter of GovHack, Australasia’s largest open government hackathon.

Wellington considers its smart cities activities as whole of city projects rather than information technology projects. The focus is on addressing issues that are a priority for the city such as building resilience, liquor regulation or anti-social street behaviour. The technology is then used to make the city more liveable for its citizens. This citizen focus also applies to Wellington’s operating environment where the council makes use of open-source software layers and core platforms which can be utilised by a range of different technology partners.*

* Smart City Hub (2017 July). Sean Audain, Innovation Officer of Wellington (NZ): ‘The key word in a smart city initiative is “city”’. smartcityhub.com/governance-economy/sean-audain-cio-wellington-nz-key-word-smart-city-initiative-city/

An updated economic development strategy is being developed by Wellington City Council, including a smart city plan as a key enabler for future capital investments.

Wellington has also worked closely with the office of the Privacy Commissioner to complete Privacy Impact Assessments on their data gathering initiatives to provide assurance that no personal identification material is collected across the sensing network.

Wellington’s investment is paying off. It won the Public Works category in the 2017 IDC Smart Cities Asia Pacific Awards for the NEC Kite flexible sending platform. In 2019, Wellington’s Virtual Wellington 3D model won the Civic Engagement category. The tool allowed people to immerse themselves in a 3D experience of the city to better understand city issues and future options.

Other smart developments in New Zealand cities

Auckland

A wide range of other smart technology has been employed around New Zealand, involving both city councils and other players.

Auckland Council launched its Safe Swim integrated web and digital signage platform which gives Aucklanders real-time information on the city water network using predictive models underpinned by sampling validation. Safe Swim won the Smart Water category at SCAPA 2018.

The council initiated a two-year programme* in June of 2018 to define what a smart cities programme might mean for Auckland. It emphasised the existing focus on the areas of integrated traffic management and digital urban planning, in addition to the public information and place management benefits systems such as Safe Swim provided. Key opportunities to be explored in the programme included circular economy developments (integrating production, consumption, re-use and re-distribution) and whole-of-life decision making, which combines connected data, analytics and high-performance computing.** An ‘Innovate Auckland’ programme was announced in 2019 focusing on waste, housing, infrastructure and food production. The Farms and Food for the Future initiative saw sensors installed to monitor soil quality and livestock growth.*** They would also be used to create a ‘digital twin’ of the farm to virtually assess the impacts of different farming practices.

* Auckland Council (2018, June) ‘Auckland’s Smart City Opportunities.’ paymentsnz.co.nz/documents/228/ThePoint2018-presentation-Matt-Montgomery-Auckland-Council.pdf

** Payments NZ (2018 June). Auckland Council: www.paymentsnz.co.nz/documents/228/ThePoint2018-presentation-Matt-Montgomery-Auckland-Council.pdf

*** Our Auckland (2019 May). ‘Farms of the future.’ ourauckland.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/articles/news/2019/05/farms-of-the-future/

In Auckland’s redeveloped Wynyard precinct two Auckland Council agencies, Auckland Transport and Panuku, partnered in a trial with Cisco, NB Smart Cities and Spark to create what has been billed as New Zealand’s smartest street: Madden Street.* The purpose was to utilise connected technology across a series of city functions including energy, infrastructure and transport, employing data and IoT technologies. A series of devices were installed along a 300-metre part of the street on car parks, rubbish bins and street lights to collect and analyse sensor data on air quality, movement and waste. The new LED lights and controls reduced energy use by up to 70%, tracked air pollution and noise levels, provided more economical remote monitoring and adjusted brightness in response to light levels. These changes are a response to the increased density of residential and commercial developments in the Wynyard area and will improve the precinct’s efficiency, liveability, resilience and safety.

* Moore, B (2018, December). ‘NZ’s “smartest street” underway in Auckland.’ ChannelLife. channellife.co.nz/story/nz-s-smartest-street-underway-in-auckland

Figure 4: Madden Street, Auckland, winner of a smart city award.

Spark also used the trial to show how IoT and 5G can help bridge the digital divide by aggregating the delivery of services and benefits, rather than relying on either more individual or manual intervention. Madden Street won the Sustainable Infrastructure Award at SCAPA in 2019 (Figure 4)

Auckland Transport’s Automated Transit Lane Enforcement project utilised Auckland Transport’s Computer Vision platform and CCTV technology to regulate and help enforce vehicle transit lane obligations. By using remote monitoring, the agency could ensure more than two people were physically present in vehicles in designated transit lanes and therefore reduce peak-time road congestion by encouraging greater public transport use and car pooling. A self-contained, relocatable camera unit integrated with Computer Vision, was used to improve compliance and ensure infringement fees were issued only as justified.

Other centres

The Smart Hamilton programme* focuses on smart society building, stimulating a smart mindset and making the most of innovation, technology and partnerships. It emphasises parking, street lighting and electrical vehicle charging as key early priority projects. It has prioritised boosting citizen participation and enhancing digital inclusion, as well as more fundamental projects, such as replacing street lights with LED bulbs — leading to both operational savings and better environmental results.

* Hamilton City Council (2018). ‘Smart Hamilton.’ hamilton.govt.nz/our-partner-projects/smarthamilton/

A number of other New Zealand councils have adopted smart technology projects including Palmerston North, Queenstown, Waitaki.

Aside from direct city functions, technology is also being deployed in a range of new and creative city-adjacent ways to respond to other social issues.

Various cities around the country have employed the forecasting service of Energy Market Services, run by national power grid operator Transpower, to better understand and plan their energy needs. The service provides half-hourly estimates of electricity usage up to two weeks in advance alongside more customisable local forecasts to allow cities to better plan and optimise usage where practical.

In Canterbury, the regional council developed a portal to aid farm management by calculating nitrogen losses to meet environmental requirements. Farm managers complete their nutrient budget information and input this data into the council tool to receive a compliance assessment.

The data company Qrious created a commercial portal which allowed tourism operators to access data from tourism information around the country. Called the Interactive Tourism Intuitive Web Portal, it produces data and analytics to give tourism operators information and actionable insights, to better cope with market growth and associated pressures.

Sensing technology is also increasingly being deployed by government agencies. For example, Kāinga Ora, formerly Housing New Zealand, plans to use sensors in their rental housing stock to measure air temperature, humidity and power consumption for the purpose of understanding how to ensure homes are kept healthy for tenants.

The Ministry of Education is also piloting sensor use in classrooms to monitor thermal comfort and noise levels so as to be able to respond to any environmental learning barriers.

After six years of participation in the Smart Cities Asia Pacific Awards, New Zealand’s IDC Country Manager said given the scale of the competition and New Zealand’s size, its results were ‘especially impressive’. She commented that New Zealand had ‘consistently excelled in the awards, establishing itself as a recognised leader in Smart City innovation.’*

* IDC (2021, March). ‘Seven New Zealand projects shortlisted in IDC’s Asia Pacific Smart Cities Awards.’

The next decade and beyond

A range of new and adapted platform technologies, portals and applications are now being progressed by New Zealand cities and towns. COVID-19 has provided both an imperative and, in some cases, a new catalyst for trials or the acceleration of digital projects. Auckland Transport implemented what has been called a world-leading development by quickly adapting their journey planner application AT Mobile to reflect the COVID-19 social distancing rules.* The Institute of Environmental Science and Research Limited (ESR), a Crown Research Institute, secured funding from the government’s COVID-19 Innovation Acceleration Fund, to look at how more effective monitoring of city wastewater could improve public health.**

* Auckland Transport (2020, October). ‘Auckland Transport’s rapid digital response to COVID-19 wins award’ at.govt.nz/about-us/news-events/auckland-transport-s-rapid-digital-response-to-covid-19-wins-award/

** ESR (2020, April). ‘ESR Scientists lead the way on Coronavirus wastewater testing.’ esr2.cwp.govt.nz/home/about-esr/media-releases/esr-scientists-lead-the-way-on-coronavirus-testing/

Other international cities have made more progress by creating real-time dashboards using smartphone data sourcing to monitor social distancing, employing digital twin technology to provide real-time visibility of assets, increasing the use of drones to aid the communication and enforcement of COVID-19 rules and using new AI-driven analytics to generate alerts for city staff via an app on their mobile phones.*

* Smart Cities World (2020, May). ‘Covid-19 accelerates the adoption of smart city tech to build resilience.’ www.smartcitiesworld.net/news/news/covid-19-accelerates-the-adoption-of-smart-city-tech-to-build-resilience--5259

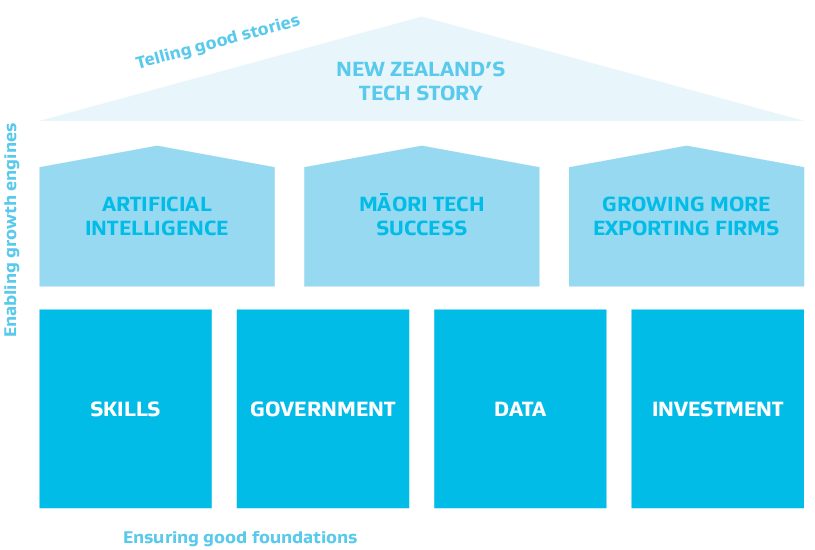

Figure 5: The Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment’s Digital Technologies Industry Transformation Plan update (August 2020).

There has been good and growing informal collaboration between New Zealand councils as they share and exchange insights on their smart activity. The Australia and New Zealand Smart Cities Council, who appointed their first New Zealand Executive Director* in February 2020, has supported this.

* Hamilton-based Jannat Maqbool was appointed. ANZ Smart Cities Council (2020). ‘Appointment of key roles for SCCANZ.’ anz.smartcitiescouncil.com/article/appointment-key-roles-sccanz

However, there remains significant disparity in the capability and capacity of New Zealand’s 78 local and regional councils to make smart progress — in addition to the dis-economies of scale caused by vendors negotiating separately with councils on the same or similar projects. This will continue to be a limiting factor on the progress the country can make progressing urban issues as the 2016 LINZ report intimated.

In its draft advice to the government, the New Zealand Climate Change Commission said the country will not meet its emissions reduction targets without ‘strong and decisive action’ involving technology and behaviour change.* A stronger and more decisive collaborative smart technology approach with our cities could greatly assist this objective as well as the other city housing, transport and liveability challenges.

* Climate Change Commission (2021, January), ‘Executive Summary: work must start now.’ ccc-production-media.s3.ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/public/Executive-Summary-advice-report-v3.pdf

The government has been working with industry on the development of a Digital Technologies Industry Transformation plan — adapting for New Zealand the successful industry transformation mapping Singapore has developed.* Singapore reports a more than doubling of the rate of labour productivity growth linked to this approach.**

* Ministry of Business, Innovation & Employment (2020, August): ‘The Digital Technologies Industry Transformation Plan: Update for Industries.’ mbie.govt.nz/dmsdocument/11638-digital-technologies-industry-transformation-plan

** Funding Societies Blog (2019, May). ‘How Industry Transformation Maps can help SMEs’. blog.fundingsocieties.com/business/industry-transformation-maps/

The draft action plan (Figure 5) focuses on the greater role artificial intelligence and data driven innovation will play. This will aid smart city activity but local government needs to be a stronger strategic driver in the plan’s implementation.

The second decade of the 21st century has firmly established a smart cities foundation in New Zealand. The opportunity exists now for an alignment with central government coordination, council leadership and private and not-for-profit sector partnership to strengthen and substantially grow this base.

leads the cities and technology business Serviceworks and he was also an elected member of part of the Auckland Council for six years. He specialises in smart city development focusing on mobility, city digitisation strategy, new technology utilisation, urban economic opportunities and citizen engagement. He is a regular international speaker and media commentator on these issues. He received the Leadership Award for Outstanding Contribution towards building Smart Cities, the Asia Smart Cities Excellence Award and was one of the Most Recommended Smart Cities Solutions Provided to Watch in 2021. He is part of the Top 50 Most Impactful Smart Cities Leaders. Mark is a member of the Smart Cities Asia Advisory Board and the Australia New Zealand Smart Cities Council’s Future of Place Taskforce. He is a director of the Committee for Auckland and the ASEAN New Zealand Business Council and is chair of the Auckland Night Shelter Trust. He was appointed by Internet New Zealand to its 2020 NZ Policy Advisory Panel.

References

IDC (2021) Seven New Zealand projects shortlisted in IDC’s Asia Pacific Smart Cities Awards

Lukas Marek, Malcolm Campbell, Lily Bui (2017) Shaking for innovation: The (re)building of a (smart) city in a post disaster environment

Land Information New Zealand (2016) Evaluation of the Smart Cities Programme 2015–2016

Stübinger, J & Schneider, L (2020). Understanding Smart City—A Data-Driven Literature Review. Sustainability, 12(20), 8460

Wellington City Council (2011). Wellington Towards 2040: Smart Capital.

Wellington City Council (2018). Smart Wellington