Local government in New Zealand has a long history of involvement and innovation in using information technology (IT) to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of councils large and small. Sadly, ratepayers have not always appreciated this and, to be fair, the costs involved in these early systems were fairly eye-watering. Back in the ’60s and ’70s the New Zealand dollar was looking pretty sad against the US dollar (the currency used for all computer sales), and to make matters worse the government imposed a 40% duty on computer imports — hardly a good example of forward thinking!

From the original colonisation of New Zealand, local government consisted of a growing number of councils and boards created to cover a range of management issues in the new towns and villages. Many of these were quite specialised and focused on such things as drainage or rabbit control. As the population grew, these entities retained their independence and even multiplied; by the mid- to late sixties there were a staggering 850 local government organisations including cities, boroughs, catchment, drainage, rabbit and other boards, all focused on a narrow range of local management functions. Clearly only a very few of these were in any position to install their own computers, especially considering that the behemoths of the time were the size of the average garage and cost more than the GDP of a small country. During the sixties, most of the small to medium sized councils used either manual systems or mechanical accounting machines, mostly Burroughs or NCR equipment. These were about the size of a washing machine and produced a spectacular clanking and grinding noise as they carried out their calculations and the huge carriages crashed back and forth. They could be programmed by means of pins and cogs to perform a series of basic calculations and to store values, but were unable to carry out a compare and branch function — essential for logic programming.

All went well until the government brought in installment rating in the early 1970s. The level of local government rates had been steadily increasing for a number of years to the stage where people, especially those on fixed incomes, had great difficulty finding the large annual sums needed to pay their rates. The government decided that people should be allowed to pay their rates in smaller installments during the year, instead of the whole lot at the beginning. This meant that the extremely resource-intensive job of getting rates accounts out now had to be repeated every couple of months. For most of the small to medium sized councils this was a near impossible ask. Councils began to consider information technology as an option to provide the necessary resource to do this job.

At that time the old mechanical accounting machines had begun to morph into a sort of embryonic computer. There were still the moving carriages and ledger cards, but the latter now sported magnetic stripes, and the machines themselves some primitive electronic circuitry for programming and working storage. You still had to have an operator feeding in the cards and to some extent entering the data by hand, so while they were more sophisticated they were still limited in throughput. Both Burroughs (now Unisys) and NCR brought out these machines and they were very popular with smaller councils.

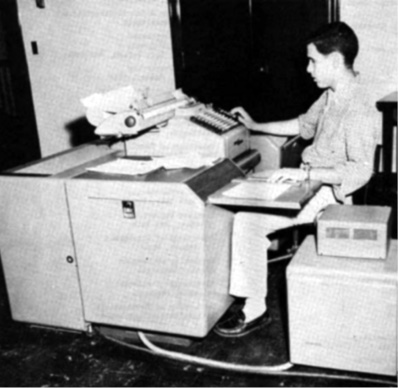

1940 Census worker using card punch.

Information technology becomes affordable

Around the same time, mainframe computer companies began to release smaller versions of their large computers. These still utilised mainframe architecture, but came in sizes smaller than a house and with a price tag many of the medium councils could afford. Palmerston North City (my own council) decided to test the market for an IT solution to its processing problems. Solutions for those other than the large metropolitan councils at that time were essentially: use a computer bureau; purchase an electronic accounting machine; or opt to go the whole hog and install a disc-based small mainframe. Those small councils and boards, and some of the larger ones, that wanted to move to an IT solution but didn’t have the wherewithal to spend large sums on equipment, generally went for one of the two computer bureaus which had developed specialised local government software. Generally, this involved batching up source input forms — meter readings, receipts etc — and posting them to the bureau. In due course, bills and lineflow reports arrived back via the post or courier.

BRL61 Burroughs E-102.

Palmerston North City decided that bureau processing was not for them, and that they should leapfrog the electronic accounting machines and go straight for the latest technology. A somewhat brave decision considering that what you got for your not inconsiderable investment was a very large roomful of cabinets — which required more tender loving care (and electricity) than a newborn baby. You also got an extremely primitive operating system, by today’s standards, and a small handful of software utilities including a COBOL compiler, after which you were on your own. Basically nothing worked as it came out of the box. You had to learn how to design computer systems then program them to do your rates billing, general ledger, debtors and the like, before they were any use at all. This took time, money and people. A major system like electricity billing or general ledger was typically a year in the making — a very tortuous and frustrating business. Both programs and input data were, in the early days, punched onto cards. The compilers were highly unforgiving — in fact we were convinced that they were openly hostile — but we got there in the end.

The early computers operated by many councils were an auditor’s nightmare. At least, they would have been had there been any auditors who understood what was really going on. Our NCR Century 101 could, by hitting one key, be stopped in full flight. Where the program was up to displayed on lights in hex, the current instruction altered by setting a couple of dials, and the whole thing set in motion again. The program thus running bore no resemblance to the printout of the original code that the auditor might rely on — and there was no audit trail to show what had happened. Fortunately, we didn’t see many auditors in those early days. One trainee auditor presented us with a questionnaire about our computer operations, one question of which asked if we removed our outer clothing before entering the computer room. Not surprisingly, this idea was received with considerable enthusiasm by my young male programmers; however, the female programmers and computer operators took a somewhat different view, and informed the rookie auditor, in no uncertain terms, that there would be no stripping in the computer room! We never did get to the bottom of the reasoning behind the question! Undaunted, our young auditor went on to become (for a very short time) Controller and Auditor General.

As I mentioned earlier, the operating systems we used back then were not highly sophisticated. Our first NCR machine used a system called B1 (3.5 kilobytes in size), which was a single job batch operating system. As our workload grew, we upgraded the hardware for a sum of money that would have bought a small cruise ship, and ran B2. B2 allowed you to run two programs simultaneously by partitioning the available memory. One of B2’s more endearing features was a complete lack of protection between the partitions. A program bug could send program one trotting happily into the space occupied by program two to the consternation of the operators, and total disaster all round. Once we had tired of the excitement caused by this feature we upgraded again and went to B3. B3 enabled us to run several partitions, all protected. Not as much fun but a lot easier on the nerves!

Of course, there were large metropolitans who dived into the large (in physical size as much as capacity) mainframes from the word go. Dunedin City was one of these, and in December 1964 installed a large ICT 1300 mainframe computer, which arrived at Port Chalmers aboard the Corinthic and was delivered to the Municipal Chambers by crane through a gap created by the removal of a window frame. It was anticipated that the ICT 1300 would be able to process the city’s rate demands in 24 hours as opposed to the week taken by the old system. Jack Randle was appointed the first Data Processing Manager, and Mavis Robinson became the first staff member qualified to operate the new machine. Input was by punched cards, and I clearly recall visiting their data entry room as late as 1970 to behold a sea of women sitting at desks entering data onto punched cards via small hand punches. The speed with which they were able to key information with these quite complicated yet very primitive devices was quite amazing. Wellington and Auckland cities had also installed IBM mainframes around the same time, and were busy developing software to carry out core accounting functions.

By the mid-to-late ’70s, Palmerston North had developed a reasonably sophisticated rating system which they had then adapted to do catchment rating, and were running a thriving business providing bureau services to a number of councils around the lower North Island. These councils gained the benefit of sophisticated data processing at a very reasonable cost without having to make the investment in hardware and software, to say nothing of the ongoing feeding and watering. Surprisingly enough this bureau work survived into the early nineties. Palmerston wasn’t the only council to do this — a number of the larger city and regional councils were supporting their neighbours in like manner.

Microcomputers make an impact

In the early to mid-eighties, the impact of the microprocessor was beginning to be seen, initially in the equipment produced by the mainframe vendors. NCR brought out its ‘I series’ machines, which were based around micro technology in the form of a look-alike mainframe, but with a very sophisticated interactive operating system, much like that of the current micro systems. Other vendors were also in this market, and NCR, Prime, ICL and Unisys all enjoyed success in the local government marketplace. There were also several systems utilising the new microcomputers, especially those which were beginning to be assembled in Asia. Based around these machines, a number of small development companies sprung up and began to create relatively sophisticated sets of software tailored specifically for the New Zealand local government marketplace. As mentioned earlier, the market, at that time, comprised some 850 potential customers so there was plenty of business to go around.

A couple of these initiatives are worth mentioning: Merv Matthews, at that time the County Clerk at the Rangitikei County Council, began to develop systems for the council, eventually completing a comprehensive range of applications which he sold to other small councils. At one time, some 50 councils were using the software. Another interesting initiative was centred around the Matamata Borough Council, where the Town Clerk, the late Bill Curragh, gathered together a large group of councils within the region for the purpose of designing a comprehensive range of basic council software. The idea was that these councils would fund development and take advantage of the economies of a single development split over all of the councils. The group called themselves the Local Government Computer Joint Committee (LGCJC), more commonly known as the ‘Matamata Group,’ and hired Auckland Computer Consultant, Ian Mitchell, to develop the software. The project was very successful and the systems ran for many years, finally being taken over and marketed by ICL (now Fujitsu).

Another very successful business working in the small to medium local government area was Napier Computer Services. NCS, owned by the Benson brothers, saw an opportunity in the local government marketplace and was an early developer of a set of Cobol-based specialised local government applications. NCS had much success in the marketplace, as did the others, but the success of these businesses relied heavily on the fragmented nature of local government in the ’70s and ’80s, with a very large number of predominantly small local authorities with even smaller budgets. In 1989, the government decided to rationalize these 850 local bodies into 85 multifunctional authorities. This had a huge impact on the system vendors, some losing up to 70% of their customers. It says much for the resilience of these businesses that all of them are still in operation, albeit some in different form from the originals.

Engineers and librarians experiment with IT

While those early developments concentrated mainly on the core financial systems, a couple of occupational groups in local government were busily trying to get themselves time on the council’s computer. These were the civil engineers and the librarians.

During the late ’70s, civil engineers were graduating with a reasonable knowledge of mainframe computing technology, having completed courses in FORTRAN during their studies. They then proceeded to make the lives of council mainframe computer operators a nightmare. A typical example in my own experience was a young engineering bursar who was all fired up with what the computer could do to help his research. He had just completed an extensive traffic survey, and had the data encoded onto ten cartons of punched cards — this is ten cartons each containing five boxes! He had spent some weeks debugging his survey analysis program, using some cards from the beginning of the last box and was now ready to run the job. He turned on maximum charm and finally persuaded the chief operator to run the job for him. With our relatively slow card reader this was about a six hour job. She finally, with great relief, loaded the final box into the reader and off it went, only to get halfway through the cards, grind to a halt and proceed to output results on the printer. In those days NCR used, as the end of file indicator, an ‘end$’ card. The engineer had replaced his test cards in the front of the last box, leaving the end$ card with them! It took the biggest box of chocolates I have ever seen to get her to run the job again!

Nevertheless, the engineers persisted and over the years many applications and packages have been implemented to cover a wide range of civil engineering areas. One of the most successful systems has been the Road Asset Maintenance and Management system (RAMM). RAMM was first developed back in the eighties, and RAMM and its associated products are still used by or on behalf of all road controlling authorities in New Zealand to provide accurate information on all forms of road assets in a timely and up-to-date manner. Similarly, there have been many other packages developed, some home grown and others developed overseas. Civil engineers and planners now have a plethora of software from which to choose.

The second group, librarians, had seen computers as the solution to many of their problems quite early in the piece. Dunedin had been running an overseas circulation package for some years when Palmerston North developed a home-grown system using NCR’s B2 operating system with online terminals connecting the mainframe to the library about 400 metres across the square. This turned out to be a major learning experience for the council IT section, as the application was running with only 32K of memory and with extremely fault prone communications provided by the old Post and Telegraph Department (P&T). I learned that everybody in the communications room at the P&T was called Dave — but when you phoned back to talk to ‘Dave’, no one had ever heard of him! Another challenge, also faced by other councils, was getting the system to run in the library bus as it chugged around town. This was solved by fitting power outlets to power poles at the busses’ regular stopping place and recording transactions on to cassette tape. There were also major issues finding terminals with enough programmability to handle the various functions such as talking to the mainframe, printing receipts, reading barcodes etc. We did solve these problems, but as I said, it was a steep learning curve, and one which most councils in New Zealand were going through at that same time.

A few years later, micro and mini-based proprietary library packages came on to the marketplace and our home-grown system was replaced by a combined cataloguing and circulation system and some more reliable telecommunications circuits.

Local authorities collaborate

As micros took over from mainframes, hardware costs started to decrease dramatically. While this made it easier for small councils to get into quite sophisticated computing, software became the greatest cost, especially (in later years) the cost of software licences.

Councils have a long history of helping each other, and this started to take effect in the IT area very early in the piece. In 1972 a meeting of those councils who were experienced in or just beginning to take advantage of the new technologies was held in Palmerston North. About 20 people turned up, most of whom seemed to be accountants (IT was seen to be an accounting function in those days), and spent a productive day discussing their approaches to computerisation. The day was hugely successful and as a result Wanganui City Council offered to host the next year’s meeting. From there, the meeting went to Hamilton then Manukau. By the late ’70s, the informal group had grown considerably, to the extent that it was decided to formalise the arrangement, and the Local Authorities Computer Services Advisory Group (LACSAG) was formed under auspices of the Municipal Association, who provided support in the form of one of their people, Graeme Marshall.

Apart from the annual meeting, the group offered consulting services to councils who wanted to move into using computer technology, or who had installed systems but found that ‘things weren’t going too well’. The mainstay of this consulting work was Ray Smith, at that time IT manager at Waitomo Borough Council. Ray spent much time running around New Zealand, helping a large number of councils to come to the right decisions.

About the time LACSAG was officially constituted, Hastings City, who were hosting the next annual meeting, asked if their vendor, Prime Computer, could demonstrate some of Hasting’s systems on a computer they would set up at the meeting venue. The next year there were three vendors, and the ‘exhibition’ as it became, now features some 50-odd stands at the annual conference.

In 1989, when local government reorganisation took place, the Catchment Authorities Association and the Municipal Association amalgamated to become Local Government New Zealand (LGNZ). It was logical for LACSAG to combine with Catchment Authorities IT group to form the Information Technology Management Group, still under the auspices of the new LGNZ organisation. All went well until a change in LGNZ Management resulted in a difference of opinion about the operation of ITMG, and the board of ITMG decided to go it alone.

The new organisation was registered as the Association of Local Government Information Management, and began to go from strength to strength. Today ALGIM employs four people in its office in Palmerston North and runs what is arguably the largest IT conference in New Zealand in Wairakei each November.

Councils differ greatly from other types of governmental or business organisations. Unlike central government agencies, they all perform essentially the same functions and in a very similar manner. Unlike commercial entities, they are not in competition with one another. This puts councils in a unique position to assist each other, especially in the area of IT. ALGIM and its predecessors have, over the years, proved this several times. When central government decided to amalgamate local and central electoral rolls, LACSAG project managed the whole operation for the Electoral Roll Commission. In spite of having a wide range of machine and input types, electoral roll data from all of the councils was collected, migrated to a standard format and input type, and updated successfully on the central government system, all within three days.

In another instance, when central government decided to hand over responsibility for parking infringements to local government, LACSAG coordinated the development of a basic batch parking infringement management system which could be used by all councils. Bearing in mind that this was in the mainframe days and software interchange between vendor equipment was virtually unheard of, the result was quite remarkable. The councils involved were running Prime, IBM, ICL, NCR, DEC and Burroughs equipment, but the standard COBOL in which the suite was written was able, with almost no change, to be compiled and run on all of the machines involved. The eventual costs to each council worked out to around $2800 — an exceptionally economical development. The project came in on time and all councils involved were ready for the changeover on day one.

In 1997, this spirit of cooperation went a step further when ALGIM and the Society of Local Government Managers (SOLGM) formed a company, Local Government Online Ltd (LGOL), to assist councils to create a Web presence. Most of the smaller councils had neither the expertise nor the funding to build their own sites, and the initial product, a standard council Web template, produced for minimal cost, was eventually adopted by about two dozen councils, many of whom are still using the system today. Shortly after the template was completed and in operation, LGOL moved into the listserve arena. One of the main problems with a large number of small councils in New Zealand, is that many council staff are ‘flying solo’ in that they are often the only person in their council with responsibility for a particular function, a professionally lonely situation. Peer level discussions used to be difficult, and finding out how other councils had handled a particular problem almost impossible, especially in a very short timeframe. The LGOL listserve system has enabled horizontal communications between peers from one end of the country to another. The lists — some 100 of them now in operation — move approximately a quarter of a million emails each month between all of the 85 councils, and have become an essential part of the information interchange between New Zealand local government professionals in all disciplines.

Local Government Online has now become the definitive local government portal, with links to all councils and an extensive local government library of good practice documents and links. The company has also developed a set of standard online interactive forms which are now being used by a number of councils throughout the country.

Recent developments

Towards the end of the nineties, most councils were beginning to contemplate the implementation of Geographic Information Systems (GIS). This was a serious investment for councils in terms of the cost of GIS hardware and software, but probably more so in the investment in human resources to code and enter mapping data into their new systems. Towns and cities began to sport multicoloured manhole covers and strange markings on the roads and footpaths as councils took to aerial photography to automate as much as possible the positions of sewers and water supply pipelines. It took many years and much financial investment, but local authorities are now reaping the benefits of having comprehensive mapping data, and are beginning to interface GIS with other council management systems as well as making this information available to the public via the Internet.

Over the last 10 years, Information Technology in New Zealand local government has moved steadily out of the realm of pure accounting. There are, of course the core accounting and financial-type systems and these are still a very important part of the IT function. They have now settled down to half-dozen or so packaged vendor systems which are being used by all of the councils. Councils, in the main, now shy away from attempts to develop their own core systems and those, in recent years, who have tried to develop these on their own from scratch have learned some very hard, and expensive, lessons!

The advent of the Internet and the Web has had a huge impact on local government systems design, and most councils are either running or in the advanced planning stages of implementing eGovernment oriented systems. Package vendors are retrofitting Web applications to their packages, and they and council IT staff are now far more outward looking in their design philosophies than they have been in the past. There is still a long way to go, and sadly many councils still consider that providing PDF forms for their constituents to print off, fill out, and post in with a cheque, constitutes eGovernment. These are the folk who have the greatest distance to travel to get to real eGovernment! Of course, bandwidth is still a major problem, especially for the rural councils, where many of their constituents have a major struggle just bringing up a Web page let alone engaging in interactive communication with their council!

Innovation in local government computing is very strong. Each year at the ALGIM conference the ALGIM Innovation Award is hotly contested — and often won by small councils who have beaten off competition from their larger and better funded counterparts to develop extremely clever systems which provide improved services to their ratepayers and citizens.

What of the future? To some extent innovation in local government computing plots a rising continuum, with the occasional sudden jump upwards, as some new technology opens the way for councils to improve services or deal with a vexatious issue they have long been struggling with. In comparing the IT innovation shown by councils over the years with the private sector, one sees that local government is clearly holding its own, at least in this area, and there is no reason to believe that this is likely to wane.

Local government computing is in good heart. Great progress is being made. Long may it continue!

is a past president and fellow of both the New Zealand Computer Society and the Internet Society of New Zealand (InternetNZ). He is a life member of the Association of Local Government Information Management (ALGIM) and is an Information Technology Certified Professional (ITCP). His career in the computer and telecommunications industry spans the last 40 years, primarily in the central and local government sectors. He has been responsible for the development of ICT strategies for a number of governmental agencies in both sectors and is a strong proponent of eGovernment. Over the last 20 years, Jim has presented close to 1000 radio broadcasts and television appearances, seminars, workshops, and training sessions, both in New Zealand and overseas, as well as authoring one of the first New Zealand books on use of the Internet for business. His interest in promoting technology use in New Zealand has resulted in his personal involvement in a wide range of IT associations, industry boards and committees. Serving on the boards of a number of IT-related companies and trusts, he has merited a number of honours, including the Communicator of the Year Award from the New Zealand Speech Board, and in November 2000 an award by the New Zealand Computer Society for the most outstanding contribution towards public sector computing in the last century.

Main reading room, University of Otago Central Library.

Hocken Collections, Uare Taoka o Hakena, University of Otago