The impact of computers on the public sector

AC Shailes, Controller and Auditor-General 1975–1983

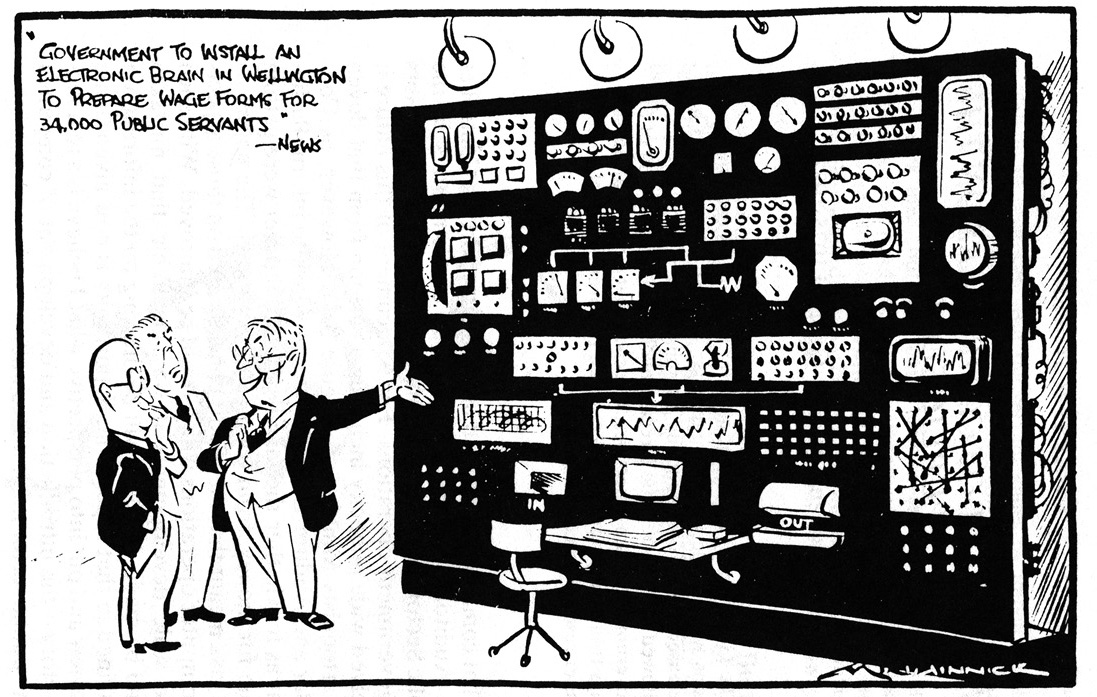

That comment, contained in my 1980 report (as Controller and Auditor-General) on ‘The Use of Computers in the Public Sector’ perhaps best sums up the impact of computers on government operations. For a document of this nature it received wide publicity including a cartoon from that doyen of cartoonists Minhinnick (Figure 3.1). However, as Controller and Auditor General it was my task to inform Parliament as to whether the taxpayer and ratepayer were getting ‘value for money’ from computer operations. The nature of that task meant that the report concentrated on those aspects of computer operations which could be improved. With such large scale developments it was inevitable that mistakes would he made. Whilst I will be drawing on the information contained in that report, the opportunity is now given to me to review and put into perspective what I believe is a real success story — the introduction and development of computing in the public sector in New Zealand.

In 1960 the year the New Zealand Computer Society was established, computing was introduced into the New Zealand public sector. Indeed it can be said that not only did computing in New Zealand start in the public sector but for the past 25 years the public sector has been the leader, and the driving force behind computer development in New Zealand. Today approximately 40 per cent of the business of the major computer firms is with the public sector. All this is not surprising, given the size of operations in the public sector compared to private enterprise.

‘It’s called the Computer-General and takes precedence over the Auditor-General.’

Central government was first to introduce computing into New Zealand when the Treasury installed a machine in 1960. During the next decade computing grew as an individual departmental function. By 1969 nine departments had computers, with Treasury, the Departments of Education and DSIR acting as bureaux for other departments. In 1970 it was decided to centralise the two bureaux operations, together with the Statistics Departments data-processing staff, into a government computer centre. This was initially set up as part of the Department of Internal Affairs with the State Services Commission handling the management and policy functions. In 1972 the operating and policy functions were merged to form the Computer Service Division of the State Services Commission.

No review of the development of computing in New Zealand would be complete without highlighting the introduction of the first major computer. The Treasury had been using mechanical accounting methods since the 1930s to cope with the large volume of work to be processed. However, in the 1950s it became obvious that existing machines would need to be replaced if overall efficiency of Treasury and departmental accounting was to be improved.

By the late 1950s electronic data-processing systems had made much progress overseas. Treasury had been following these developments and in May 1957 IBM Australia submitted to Treasury its proposal for the installation of an IBM Type 650 Data Processing Centre. This proposal was accepted by the government in 1958, installed in 1960 and The Impact Of Computers On The Public Sector 39 officially opened by the Minister of Finance The Hon. HR Lake on the 23 March 1961.

The computer system installed in the Treasury made available for the first time in New Zealand the speed and versatility of a stored programme machine using magnetic tape. The biggest single job initially undertaken was the payroll preparation of some 34,000 public servants. The computer worked out all entitlements, calculated tax and superannuation deductions, and stored the results on magnetic tape as a permanent record of the amount of pay due until an amendment was made. Each fortnight the tape record was used to print the pay vouchers and produce punched-card cheques as required for all pay points, together with coin analysis as required. Other essential records such as year-to-date totals and deduction statements were also prepared as part of the pay run. It is a tribute to these initial pioneers, and to those who followed, that for the past 25 years public servants have never missed being paid on due date.

But the introduction was not without its hiccups. As a Treasury officer at that time I can the remember the upheaval caused by the installation the new machine. As the machine was stated to generate as much heat as 80 one-bar electric heaters, an air conditioned room had to be provided, with a dummy floor to take the cables connecting the machinery. Standby generating equipment was also needed. In its initial stages the machine broke down frequently and it was only stalwarts like Paul Walker or Laurie Peko who had the magic touch necessary to get operations going again.

One must also pay tribute to the policy advisers and decision makers at that time. Little or nothing was known about electronic data processing and it took considerable courage to put their trust in a machine and abolish tried and tested clerical procedures. But senior Treasury officials were convinced that computers were here to stay, and their foresight has been amply justified during the past 25 years. The Controller and Auditor General at that time, in commenting on the computer introduction stated:

That these modern accounting methods are a far cry from those employed in the days of King Henry 1, when the King’s finances were controlled by a small group of administrators selected from the baronage and the clergy. This body constituted the Exchequer, so called from the chequered tablecloth used to facilitate the counting of money.

During the 1960s computer installations continued to increase and by the end of the decade nine departments had computers, with many others using the Treasury and Education Department installations as bureaux. The government applications now covered the public accounts and central pay system, accounting systems of trading departments, and other systems processed on departmental equipment in Social Security, Post Office, Railways, DSIR and Ministry of Defence. However, it was becoming apparent that one means of obtaining the maximum benefit from EDP was the pooling of resources to form a bureau to serve all. This was particuarly apparent with local bodies, where such a move would avoid separate expenditure on sophisticated accounting machines that would undoubtedly exceed the individual contribution required to a joint bureaux.

I will be discussing local body developments later but the principle of pooling resources was recognised by the government, in establishing in 1970, the Government Computer Centre to centralise most government data processing. During 1970 the electronic data processing, conducted by the Treasury and certain other Departments, was transferred to the Government Computer Centre, an independent unit within the structure of the Department of Internal Affairs. The centre took over the Treasury and Education Departments’ computers and also acquired an additional one. It provided all facilities, i.e. system design, programming, data preparation, and computer processing for most government departments. Policy was subject to the control of an interdepartmental committee, the EDP Co-ordinating Committee, chaired by the chairman of the State Services Commission. However, in June 1972 the government decided that the State Services Commission should assume responsibility, not only for policy, but operation of the Government Computer Centre, and to facilitate this, established a Computer Services Division, responsible to the chairman of the commission. This new division was now responsible for carrying out all data processing for government departments except the Ministry of Defence, Post Office, and Ministry of Works which retained their own organisation and equipment.

The Computer Services Division has now developed into a highly centralised operation, running four large computer centres and four data preparation centres. The Ministry of Works and Development Computer is now owned by the State Services Commission but operated by the Ministry as a specialised engineering facility. Other large independent installations are operated by the Post Office, Department of Health, New Zealand Railways Corporation and Ministry of Defence. All these installations have data communications networks, some of which are extensive. Several other departments have small computers, some linked to the main CSD computers.

Widespread use of computers in the public sector has only occurred during the past ten years or so, but in that time there has been rapid expansion in the use of computing and consequent increases in expenditure and the number of staff employed. Today the public sector employs some 3000 data processing staff, approximately a quarter of New Zealand computing personnel. The Computer Services Division itself (450 staff) has an enviable record of success and is now recognised within government, in the private sector and internationally, for its achievements. The Computer Services Division:

Advises government on computing matters and on new developments.

Reports to government on departmental proposals and other submissions.

Co-ordinates electronic data processing in the the public service by maintaining the CSD as an operating division, by performing central purchasing activities, by emphasing strategic planning, and by insisting on adherence to a standard methodology for managing projects.

Provides electronic data processing services, including full application, design and development skills, support services and local and remote computing facilities.

The basic aim pursued by CSD is to ensure that the effective and efficient utilisation of all their resources will result in a reduction in the cost of public administration to the New Zealand Public Service. However, its two primary functions of ‘control’ and ‘service’ are coming under increasing scrutiny. In my 1980 report it was recommended that the control function of CSD be separated from the operation and the advisory role, either by a separate operating division within the State Services Commission, a separate agency, or a Government Services Department combining processing operations with other service functions. The tasks of initiation, evaluation, decision and implementation of all or even the majority of departmental computing projects is possibly beyond the capacity of any one organisation. It is indeed gratifying to note that the State Services Commission is undertaking a further review of its computing operations.

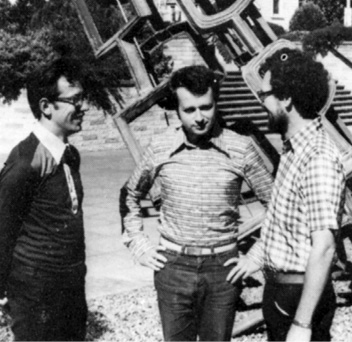

New Zealand has gained pre-eminence in advanced programming techniques. In 1977 this group of international programming specialists gathered at the Ministry of Works as part of an international research scheme to develop natural language programming.

Each major computer installation provides services for its own sector of government operations. The Vogel Computer Centre is operated by the Ministry of Works and Development as a service for the engineering and some of the scientific work of all government departments. This operation is under contract to the State Services Commission. The ability the computer gives — enabling more alternatives to be considered in depth — is a valuable one, both technically and economically. Increasingly tasks have more constraints and complexities, and computer support is essential if feasible solutions are to be found. Facilities have been extended to give on-line support and national coverage for technical offices of the Ministries of Works and Development, Energy, Post Office, Broadcasting Corporation of New Zealand, Department of Scientific and Industrial Research, Railways Corporation and Forest Service.

It is worth considering in a little more detail the use that has been made of the Vogel Computer by the Ministry of Works Looking Back To Tomorrow and the Electrical Division of the Ministry of Energy. I consider that this is where the real value of the use of a computer can be readily understood and demonstrated, often with spectacular savings. It is also worth recording that this is the area where the government spends substantial amounts on capital construction each year. I have no doubt that computer applications in other areas have been equally successful but these are often more difficult to quantify.

The objective for the use of computers in the Ministry of Works’ technical activities is an improved final project, not a cheaper, faster or simpler technical process. In most cases the cost of the use of the product is at least ten times the cost of construction, which in turn is at least ten times the cost of the design process (e.g. Figures from the New Zealand Year Book show the expenditure on petroleum and motor vehicle imports to be approximately twelve times the expenditure on roading.) Design processes generally involve analysis, information handling and technical judgement based upon experience and intuition. In this the particular abilities of both the professional and the computer are required and these are generally complementary. Here the computer is a tool giving the user the opportunity to gain a wider and more accurate understanding of the problem and the ability to test the effect of different solutions.

The development of computer support in the Ministry was vested in a Computer Services Section set up in 1966 from the Systems Laboratory, Central Laboratories and the Machine Accounting Section from the Accounts Division. Program development was started and in the late 1960s a new computer installation was established in the Vogel Building. This machine was initially shared with engineers from the then New Zealand Electricity Department. Today surveys show that the economic return from the use of this computer outweighed by a factor of at least eight to ten the cost of the computer and its operation.

Here are three examples, the first from Power Canal Design. The Hydro-electric power stations in the Upper Waitaki Power Scheme are supplied with water by canals.

This means that the time water takes to flow from the inlet to the station and the surges that accompany rapid changes in generation must be accommodated within the canal. Accurate prediction of the water surface is only possible by computer. Such predictions save unnecessary embankment costs and also allow station operation rules to be set up that give the most efficient performance for the generating system. Such rules were set up for the stations in this scheme and are producing ongoing benefits of over $2 million per annum.

Another area with high potential savings is that of selecting the optimum route for roads etc. The relocation of the State Highway between Cromwell and Clyde and associated local roads for the Clutha Valley Development Project have been designed using computer based methods. Ten alternative routes have been considered in depth where perhaps two could have been considered by manual methods. The savings in cost associated with reduced earthwork quantities between the best of the first three alternatives and that selected is $1.5 million at current contract rates.

Finally there is the case of the Mangaweka road-rail deviation. The following press statement at the time (early 1970s) still makes an interesting story —

Delays in construction programmes usually mean vastly increased costs but in the case of the Mangaweka road-rail deviation it has meant the saving of millions of dollars. If a planned deviation had gone ahead in 1967 it would have cost about $9 million and about $11 million at the present day costs. But thanks to the Ministry of Works computer a comparable route has been found that will cost only between $6–$6.5 million. Ministry engineers using the computer have also found an alternative road route which closely follows the present road. If this route is adopted and the National Roads Board does not have to join the Railways Department on a joint road-rail deviation on the other side of the Rangitikei River it would save the Board even more. The Board’s share of the cost of the original $11 million proposal would have been about $6 million and about $3.5 million of the $6–6.5 million plan. But if the Board goes it alone it will only cost it between $1.7 million and $2 million. Thus the computer could end up saving the Board about $4 million. The computer, which has been in use for little more than a year, is able to provide from aerial photographs an infinite number of trail lines which can be varied laterally or up and down. When programmed with desirable gradients and other controls the computer provides a solution which requires minimum earth works. It is impossible for engineers to get similar results using conventional methods unless they are prepared to spend decades doing surveys.

Computers have come in for considerable abuse over the years but as far as the Ministry of Works is concerned the one it has is worth its weight in gold.

The other initial major user of the Vogel Computer was the New Zealand Electricity Department (now the Electricity Division of the Ministry of Energy). The design, development and forecasting areas of the Division’s activities are the major users of the computing facilities provided by the Vogel Computer Centre. While detailed designs of major items of electrical equipment, i.e. generators, transformers and circuit breakers or associated mechanical items such as turbines and boilers are not undertaken by the Division’s staff, a considerable amount of additional work is necessary on ancillary parts of the system to incorporate these predominantly overseas-cost components.

In the development of a power system the basic plan for future generation is dependent on the ability to forecast the country’s electrical power demand for a considerable period into the future, taking into account such factors as weather, the country’s general economic situation and any effects or alterations to tariffs.

Assessments of the results produced by present-day computer-aided methods compared with earlier manual methods are impossible to make accurately as the techniques currently being used could not be applied manually — certainly not without gross assumptions which would render any comparisons of doubtful value.

Power development is a typical area where investigation of alternative generation developments is greatly assisted by use of the computer, because many more combinations can be analysed in greater detail. While there are frequently other considerations which may dictate that the optimal solution is not proceeded with, these analyses provide the background information on which management decision can be made, in that the penalty of non-optimal development is known. Byproducts of these long term investigations are that, for shorter-term work, marginal costs of generation are obtained and also scheduling of fuel for thermal stations (coal, gas and oil) can be achieved more accurately. Forward projections of gas use are essential to tie in with overall fuel use for the Energy Plan and developments of the gas/oil resources. During the simulation of the operation of all stations for the planning period, other factors are obtained (plant factor, necessity for two-shift operation) for future stations and these details can then be written into the station and equipment specifications in the planning stage, rather than possibly having to modify multi-million dollar contracts later.

In the design and construction area the Power Project Co-Ordination Section makes use of the ICES-PROJECT subsystem for scheduling construction on the major power station schemes. It was used for Huntly Power Station and it is proposed to use it for Ohaaki. These have capital costs of $500,000,000 plus, and $200,000,000 respectively. The importance of keeping construction on schedule and the savings which can be achieved by good control of the projects can be quite considerable.

Other design areas use the computer for analysis of station earth grid design (to limit step-voltages and rise of earth potential under fault conditions), analysis of conductor catenaries for take-offs from station structures to transmission lines and analysis of strengths of structures. In addition the effect of using filters on the South Island system to limit the transmission of harmonic frequencies from the High Voltage Direct Current scheme and from the Tiwai smelter, has been modelled successfully and this application has been used on the North Island system to study the consequences of North Island Main Trunk electrification.

Moving away from the question of engineering design we come to what is undoubtedly the most well known computer installation as far as the general public is concerned, the Wanganui Computer Centre. The centre is operated by the CSD for its three main clients, the Police Department, Department of Justice and the Ministry of Transport. It provides and operates, as required by the Wanganui Computer Centre Act 1976, a computer based information system to aid its three main clients in carrying out effectively their roles in relation to the law and administration of justice, at the same time ensuring that no unwarranted intrusion is made upon the privacy of individuals.

The services provided include a rapid response on-line information update and retrieval operation for over 25 major systems 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Through its 403 terminals the centre deals with 90,000 transactions a day and switches 15,000 messages a day between terminals. This centre is still expanding rapidly. For example, in 1983 Parliament agreed that the centre store information and licence details of all firearm owners in New Zealand, some 350,000 of them. The Department of Health commenced a major computer project in 1975 designed to provide all hospital boards with core computing systems. The initial proposals were for three core systems, i.e. payroll, patient admission and discharge recording, and clinical laboratory. The project encountered considerable technical and managerial difficulties, but in 1981 an agreed alternative strategy was developed under an advisory board. Considerable progress has been made by the Department, computing services are now provided to all but the very small boards. The co-ordination of development through a single advisory board has been an essential element of ensuring that duplication of effort is avoided while at the same time allowing local initiative.

Progress on the major systems are —

Payroll — Study of other payroll systems showed that the current system best suited the needs of management. It provides personnel recording and manpower budgeting facilities and is now used by 20 boards, with probable extension to the remainder in the near future.

Admission/Discharge — This system now covers over 40 per-cent of all admissions in public hospitals. It is seen as the base for future hospital and patient management systems.

Clinical Laboratory — Development of a national system was halted in 1980 and boards have now been authorised to proceed with development of their own systems after consultation with the Department of Health.

The Computer Service Division also maintains and operates computers at the Trentham Centre and in Wellington at the Cumberland Centre and Pipitea Centre. These centres service most government departments.

The data processing work of the Social Welfare, Valuations Departments, and the Housing Corporation are accommodated in the Pipitea Centre, whilst all of the government accounting functions, public service and teachers’ pay as well as the two major insurance companies, State Insurance Office and Government Life, are catered for by Cumberland Computer Centre. Out in the Hutt Valley, Trentham’s Computer Centre provides a remote processing service to a number of departments together with a major on-line transaction processing activity (known as the CASPER system) meeting the requirements of the Customs Department import entry activities. All of the CSD centres have well established data communications networks which extend from Kaitaia in the north to Invercargill in the south.

It would not be possible to review all these operations here, but perhaps the activities undertaken for the Inland Revenue Department can be taken as typical.

It has been suggested that if the Inland Revenue Department wished to carry out manually what is now done by computer, it would need a staff approaching the total population of New Zealand. That is obviously an exaggeration, but the work performed at the Pipitea Computer Centre of the CSD for the Inland Revenue Department is most impressive. Inland Revenue is the single biggest user of the Pipitea Centre’s resources, and during the peak months of activity between April and August will process up to 140,000 transactions against the data-base each night and make 40,000 records information in respect of two million tax returns each year from salary and wage earners, self-employed, companies, estates, etc., and automates the policing action in respect of persons failing to submit returns. It also:

Calculates tax due or refunds payable from summarised totals captured from salary and wage earners returns.

It automatically posts debits or credits to the ledger and produces cheque or payment demands. Suites of programs associated with this system police for payment on time, send reminder notices, and assess penalty tax.

Collects PAYE instalments in most cases on a monthly basis from employers — more than $500 million per month in 20,000 transactions, including arrears, recording and policing for payment. Matches four million IR12 tax certificates from employers with four million submitted by tax payer with their returns. Levies all employers based on number of employees and the occupations they are employed in, for Accident Compensation.

It is interesting to note that the system recovers an additional $6–8 million per year from those who ‘forget’ to declare all income. It also isolates employers who have deducted PAYE but not passed on deductions to Inland Revenue. There is a large volume of routine clerical work involved in processing tax returns. Computerisation has stream-lined and speeded up the whole system, taken much of the drudgery out of the work and freed employees for more interesting and important duties.

Another large group of users of computers are the statutory boards and corporations. These cover primary products marketing boards, other statutory corporations like the Broadcasting Corporation, and wholly government-owned companies. As noted in my 1980 report, these organisations employ approximately 450 data processing staff and they possess computers valued at a fifth of the total in the public sector. Computing in statutory boards and corporations is characterised by a wide range of applications. Many are specific to the functions of the organisations. There is a number of factors which make their data processing operations more like those of commercial companies. They have experienced similiar problems to those in government installations, but they have been able to minimise the effect of these problems by use of additional resources at short notice. This may involve employing extra staff, hiring consultants, or purchasing additional hardware. This is possible as boards and corporations do not have the lengthy approval processes that exist in central government and are able to readily adjust budget allocations.

Their managers have tended, through a commercial orientation, to be more aware of the strengths and limitations of data processing. In addition, several boards and corporations have made extensive use of consultants. Their experience has generally been more satisfactory than in the remainder of the public sector. This is probably indicative of the closer relationship of applications to the commercial experience of the consultants.

The picture in the local government area is somewhat similar but the initial computing requirements of most local bodies were met by computer bureaux. The experience gained from their services and the fall in hardware costs led to a growth in facilities within organisations. Currently, the value of computers owned by local authorities represents approximately 20 per cent of the total value of computers in the public sector and they range from very small, unsophisticated computers to medium-sized machines. Local authorities employ approximately 800 data processing staff.

The traditional requirement of local government has been for financial applications and the majority of effort has been in this area. Other applications include electoral rolls, libraries, scientific/engineering and port container tracking. Local government computing is not homogeneous. There is a wide range in the size of installations and marked variations in standards. This is the result of reliance on the ability of individuals within the data processing area with little top managerial direction or interchange of systems between local authorities.

In my 1982 report to Parliament, I reiterated the view that it is of benefit to local authorities to co-operate in the joint development of computer systems. While joint operation of a bureau may not now be cost-effective because of the relative cost of large mainframe computers as compared with micro computers, there is a considerable advantage in joint purchase of hardware, and joint purchase or development of software. It is pleasing to note that a number of local authorities have already participated in the joint operation or use of computers. For example, during 1981 a group was formed based in the Matamata Borough Council. Market proposals were evaluated but the group considered that best results could be achieved by having separate contracts for purchase of hardware and for custom written software. I am sure this system will provide a useful additional option to local government managers. Indeed it has grown into a group of 31 local bodies operating as the Local Government Computer Joint Committee. Almost all evaluations of computer proposals are now being assisted by members of the Local Authorities Computer Services advisory group.

Future computer developments in local government need to extend the use of the computer as a management tool rather than as a means for performing basic bookkeeping functions.

All the computer installations reviewed in this paper and particularly their financial applications, are subject to audit by the Audit Office. This has meant a very significant change in the modus operandi of the Audit Office in the past 25 years. In every case when a new computer installation is planned the client consults the Audit Office to ensure that adequate controls have been included in the programme. The Audit Office in turn has had to ensure that it can effectively play this role, and, to this end, EDP auditing courses have been conducted since 1960. These courses are often attended by staff of client departments and by chartered accountants in public practice. There is no doubt in my mind that the Audit Office over the past 25 years has been to the forefront in New Zealand in training EDP auditors.

Whilst I was Controller and Auditor-General it was always my concern that some major computer fraud would be uncovered. It is a tribute to the high skill and training of the auditors and the EDP staff of our clients, that New Zealand seems to remain free from such white-collar crime, now becoming so commonplace overseas. To keep it that way we must ensure that our computer systems and controls are one step ahead of the would-be criminal.

My 1980 report on the ‘Use of Computers in the Public Sector’ was designed to assist clients in avoiding many of the more common pitfalls in computer installation and application. The report has been well received and most of the recommendations adopted. But we do not stand still. Readers who have persevered so far will by now realise that the writer is not a computer expert. (Indeed much of the information contained in the paper has been kindly supplied by officers of the CSD Ministry of Works and Audit Department.) Most government administrators and decision makers of my generation have had to rely on advice and guidance from computer experts. Times are, however, changing. The new recruits into government offices today are very knowledgeable on what computers can do. They will expect and demand that they be able to use computers in their everyday work. Similarly the cost of hardware, once the main cost, is now only a fraction of the cost of the human resources needed to operate computers — a trend which will undoubtedly continue. In the short term there is a growing and widespread interest in computer based management information systems. Associated with this interest is a concern that computer systems are not in place to meet demands in this area. These demands have no doubt been created by the changed emphasis in government, emphasis on cost performance, on improved control of resource use and on a need for better reporting.

In a recent State Services Commission study on the introduction of information technology into the New Zealand Public Service the benefits perceived were:

Improved management support and financial savings from increased efficiency. Better access to and dissemination of information which will improve communications both internally and with the public in general.

In the next ten years managers and decision makers will have on their desks ‘decision support systems’ as familiar as today’s telephone.

In the following 15 years — who knows?